SONA

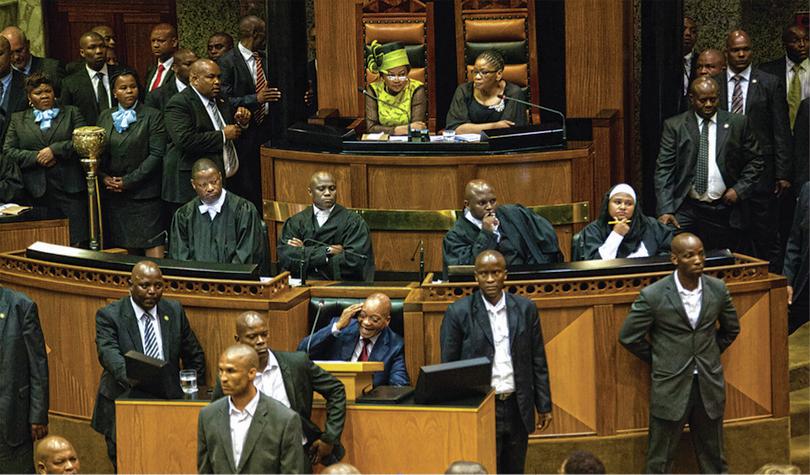

Nobody will remember what President Zuma said in his 2015 State of the Nation Address. That’s because the occasion became “The day our country broke”, to quote Ranjeni. After repeatedly interrupting official proceedings with chants of “Pay back the money”, the EFF stepped up the verbal pandemonium that would, within minutes, spill over into physical cross-party violence.

The former president of South Africa laughing while chaos envelops Parliament and angry voices fill its chambers.

The former president of South Africa laughing while chaos envelops Parliament and angry voices fill its chambers.

Source: Greg Nicolson

For the millions of South Africans listening to and watching the live broadcast, this was the day we saw an earthquake tear through what we thought was inviolable: the supposedly sacrosanct institution of the democratic Parliament.

“No matter what happens, no matter what those in authority say or do, South Africa will never be the same again. It was meant to be a solemn annual event in the life of our nation: the opening of our Parliament, the presentation of the State of the Nation Address by our President, the continuation of a journey Nelson Mandela began in 1994. We are now forever damaged by the people we stood in queues to vote to represent us,” wrote Ranjeni.

“On Thursday night, it was difficult to see who represented us. Not the people who decided to curtail the right to information, not the people who set out to cause chaos in Parliament, not the MPs who applauded the violent assault and removal of other MPs, not the president, who brought this shame on our country. They all broke us.”

As the House hit the skids, Greg caught imagery of stony-faced former presidents Mbeki and De Klerk witnessing the bedlam.

In one of the most shocking aspects of a shocking event, cellphone signals were initially deliberately jammed within the National Assembly. But on her phone, Ranjeni filmed riot police unlawfully storming into Parliament.

A day later, investigative journalist Julian Rademeyer broke the story behind the physical manhandling of MPs by security forces for Daily Maverick.

“A Public Order Police officer, who appears to have played a leading role in forcibly removing Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema and other EFF MPs from the State of the Nation Address this week, has boasted on Facebook of a ‘hunt for Juju’ in the ‘once hallowed halls of Parliament’,” wrote Rademeyer. “Wearing a black Hugo Boss suit jacket, Captain Walter Prins led a phalanx of white-shirted ‘security forces’ into Parliament on Thursday after they were instructed to forcibly remove Malema and two other EFF MPs from the House.”

Marianne Merten describes seeing the “bouncers” before SONA began. “The first indication that something was being cooked up by the government’s security honchos were the white-shirted, black pants-wearing bouncers with their ‘high risk’ tags – some of them were seconded from the riot police as the public order police,” she says. “I remember milling about outside, and watching them march in formation into Poorthuis, a main entrance. Then came the discovery of the signal jammer in the House, another first in democratic South Africa.”

The repercussions of SONA 2015 are still being felt today, in an increasingly securitised parliamentary atmosphere. Says Merten: “Rules were rewritten to eject rowdy MPs, and bouncers became a permanent reality as police officials were recruited at short notice to fill the chamber support officer posts that had been created in the parliamentary organogram. It’s a legacy that in many ways remains uncomfortable for many working at Parliament, and still reverberates in the labour court action by long-standing PPS members against the better terms and conditions of service enjoyed by the bouncers who were hired at higher salaries.”

“The fact that this move was premeditated elevates the bad taste in the mouth of SONA 2015 to full-blown halitosis.”

For the media, the use of signal jammers in the House represented a deeply troubling attack on press freedom. The fact that this move was premeditated elevates the bad taste in the mouth of SONA 2015 to full-blown halitosis. Greg Nicolson explained in his story, “Jamming in the house of no regrets”:

“There seems a clear motive to use a jamming device in the House during SONA. The EFF were likely to disrupt the speech. If they didn’t relent, party members could be evicted from the House. That would embarrass President Zuma and the institution. So the parliamentary feed would likely be cut or diverted if there was any violence. But members of the media could provide the public with live footage, audio and images from their phones – if they had signal. Easy to solve – bring in a jammer and cut it to save face and hide the bad story to tell.”

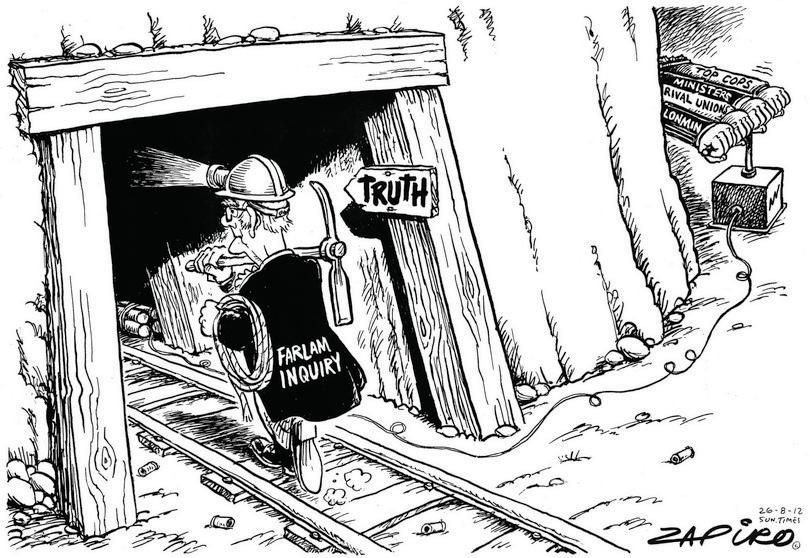

Filing at Farlam

Chaired by retired Judge Ian Gordon Farlam, the Farlam Commission of Inquiry’s mandate was to “investigate matters of public, national and international concern arising out of the tragic incidents at the Lonmin Mine in Marikana in the North West which took place on about Saturday 11 August to Thursday 16 August, 2012”, leading to the “deaths of approximately 44 people, more than 70 persons being injured, approximately 250 people being arrested”.

Or, in layman’s terms: to find out how the hell the Marikana massacre could ever have happened.

The Farlam Commission’s work stretched deep into 2015. Several Daily Maverick reporters filed exhaustive reports on witness testimonies and, ultimately, the findings and recommendations of the commission report, released in mid-June that year.

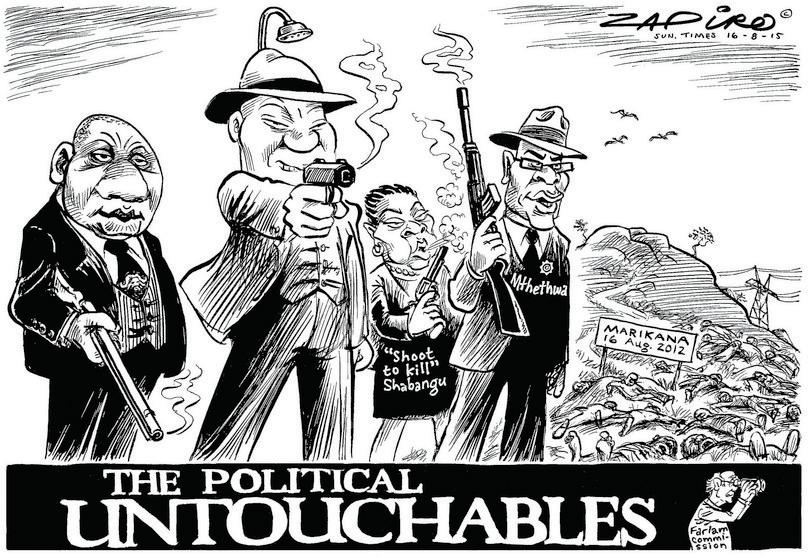

“President Jacob Zuma finally released the report of the Marikana Commission of Inquiry on Thursday. Political figures were exonerated but Police Commissioner Riah Phiyega’s fitness for office was questioned,” wrote Greg Marinovich. “Those who committed the killings, both police and strikers, as well as Lonmin’s failure to protect employees, should be investigated, the commission found.”

Although it did not buy police versions of what happened at Small Koppie, and there “were no cartridges found at scene two that could have been fired by the miners”, the report stated that the “lack of clarity around the death of the 17 deceased persons at scene two, places the commission in the difficult position of not being able to make findings as to the circumstances surrounding the death of each deceased… To accept or reject any version, with any degree of certainty, requires further interrogation of many factors.”

In fact, the report, although devoid of the ballsy pronouncements this case arguably required, offered a damning assessment of police obfuscation.

“The South African Police Service provided no details of what happened with regard to the deaths of most of the deceased at scene two,” it said. “Where it does provide evidence pertaining to the deaths of some of the deceased, their versions do not, in the commission’s view, bear scrutiny when weighed up against the objective evidence.”

To launch a full investigation – “with a view to ascertaining criminal liability on the part of all members of the [SAPS] involved in the events at scene one and two” – the report recommended that a “team is appointed, headed by a senior state advocate, together with independent experts in the reconstruction of crime scenes, expert ballistic and forensic pathologist practitioners and senior investigators from IPID, and any such further experts as may be necessary”.

Recommendations also urged investigating the “strikers with weapons against the Dangerous Weapons Act and Gathering Act”, plus the establishment of a panel to “review public-order policing and analyse international best practice”.

Seven years have ticked by since that horrifying day in August 2012 shook the very soil of South Africa. A full commission of inquiry has come and gone. Phiyega lost her job in October 2015, yet most of the commission’s findings appear to be suspended in some kind of a phantasmal zephyr, variously wafting between apparently interminable deferment, interminable denial and interminable irresolution.

Yet Daily Maverick’s commitment to demanding accountability has been consistently felt in the voices of various reporters and commentators, not least of these being Cees de Rover – SAPS expert witness at the commission as well as a senior adviser to police forces in more than 60 countries across Africa, Asia, Europe and South America. De Rover also sat on the official panel of experts advising SAPS on critical issues of reform.

“The findings of the Marikana Commission of Inquiry have been very clear. Yet six years after Marikana, the SAPS is yet to change,” reported De Rover in early November 2018. “I believe the panel of experts has been thorough and comprehensive in the completion of the work entrusted to it. That work finished in February of this year and a report of the panel’s work now rests with the Minister, as do the myriad recommendations, for reform of SAPS, contained therein.”

De Rover’s was a fly-on-the-wall lament that provided clue of exactly what the SAPS appears hellbent on avoiding – the reckoning with its own chaotic failings; having to offer an unconditional apology to the people of Marikana and the public at large; and delivering to public scrutiny its ostensible attempts at transformation, particularly in the field of public-order policing.

“With growing frustration, I have sat on the panel of experts the last two years since April 2016. With mounting incredulity, I have witnessed the blatant unwillingness of the SAPS to heed any of the recommendations of the commission of inquiry, or to acknowledge their merit. This includes attempts to put up for discussion the veracity and validity of the findings of the commission.”

But on the Marikana massacre’s scale of spectacular incomprehensibilities, the murkiest seems to be the Transformation Task Team appointed by the police ministry to implement the expert panel’s recommendations.

“Can you still follow? Recommendations for a fundamental overhaul of SAPS organisation and management practices in general, and public-order policing practices in particular are handed to a team that has a majority of SAPS senior management as members – who stand to be affected by the changes proposed – and is chaired by someone [a priest] whose credentials have nothing to do with law enforcement,” De Rover points out.

Aside from the task team achieving “nothing at all”, for Marinovich the biggest unresolved questions four-and-a-half years after the commission’s conclusion involve charging “individual shooters” from the SAPS.

“If there is not enough evidence to isolate more than just a couple like Major General Ganasen Naidoo, they should be charged under the common purpose doctrine, just like the surviving miners were charged in the immediate aftermath of the massacre,” he says, referring to the “common purpose” law invoked by the NPA in August 2012 to charge 270 miners with 34 counts of murder each. The charges were dropped that September, after a national outcry. “Dan gaan die poppe dans, and the truth will finally emerge as cops try to save their butts.”

In other words, it may be possible to lay criminal charges at the doorstep of the state, as well as the mining industry at large for failing to address the institutionally violent and fomenting conditions to which black migrant labour has been subjected for decades.

Marinovich in his commission reporting called Farlam’s recommendations “legally and socially conservative, and morally weak”. If nothing else, says Marinovich, we have here a perfect illustration of democratic South Africa’s history of hollow commissions of inquiry. These are a “typical” consequence of a state wanting “to buy time and delay consequences” – even where commissions have a vital role to play in the substantive recovery of the South African story.

Marikana’s significance remains unquestioned. Interviewing Marinovich in 2017 after the journalist had just won the prestigious Alan Paton award for his book Small Koppie: The Real Story of the Marikana Massacre, Greg Nicolson heard that Marikana was a point of no return.

“If the state can get away with murdering 34 people in a day, and publicly lie about it, it’s no surprise leaders haven’t taken accountability for the exposures of the Gupta email leaks.”

“The bar was lifted on what they can get away with publicly,” Marinovich told him. “If the state can get away with murdering 34 people in a day, and publicly lie about it, it’s no surprise leaders haven’t taken accountability for the exposures of the Gupta email leaks.”

The massacre and murders, says Khadija now, “forced South Africa to reckon with a part of itself that it often ignored”.

“Marikana abused South Africa of its naivete and innocence. What it did was strip away our pretence, about who we thought we were. It showed up an ugly side of us. That was the thing that struck me driving to Marikana every day. How different it felt in Johannesburg, compared to life in Marikana.”

Nonetheless, in South Africa we are still grappling with how to protect the most vulnerable in our society.

“Marikana is just one example of this malaise – the truth of Marikana is that it changed everything and it also changed nothing,” she observes. “If anything, I do hope that we as journalists continue to do the important work. You’ve done something right precisely when people respond with disbelief. We need to keep probing and we need to do that more consistently. What we have to do better as a society is hold to account those in power. We are just one incident away from another Marikana. That’s our reality – a police service that behaves like a law unto itself.”

For now, South Africans can, and probably should, assume that anything is still possible in the “Never, Never and Never Again” land that Nelson Mandela envisaged in his 1994 inaugural presidential address at the Union Buildings in Pretoria.

“I think we have seen that the police – even under what is a reasonably mature democracy 20 years on – believe they serve the state first, the ruling party second and citizens last,” says Marinovich. “Of course Marikana can happen again.”

And we all fall down…

“On Thursday evening, below the dramatic backdrop of Table Mountain, the statue of Cecil John Rhodes rose from its plinth, teetered in mid-air, and was then lowered onto a flatbed truck that drove it off to a place of safety. University of Cape Town (UCT) students whipped the statue and covered it in red paint as others cheered and ululated. It was the final moment of ignominy before the statue disappeared from public view,” Ranjeni reported in early April.

Although the UCT statue of Rhodes may have fallen, this was to be just the beginning of a wave of student protests that would sweep the nation in the most sustained period of youth activism since the 1970s. Ranjeni suggested that its genesis could be traced to one politician in particular: “Now there are raging debates about heritage, race and the pace of transformation. But let’s not forget who started this. #RhodesMustFall was driven by the UCT Student Representative Council (SRC) but it is Julius Malema who planted the seed. What this saga has shown is that, politically, nothing is set in stone.”

The ensuing #FeesMustFall student-led protests, agitating for increased government subsidies towards tuition fees, came to a head in late October when thousands of protesting students flooded into the parliamentary precinct and were brutally forced back by police.

In “#FeesMustFall: The day Parliament became a war zone”, Rebecca, fellow staffer Marelise van der Merwe and a freelance photojournalist recorded their experiences on a day when “the only noteworthy aspect of the parliamentary schedule was supposed to be the tabling of Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene’s midterm budget review. Shortly after 2pm, everything changed. The legislature became, for a few brief moments, the ‘People’s Parliament’ it is often touted as – before it exploded into a battlefield”.

As South African journalists, getting caught up in protests is nothing out of the ordinary. But for Rebecca the emotional impact of witnessing this #FeesMustFall protest at Parliament was hard to shake off.

“I remember sheltering from police beside a car next to a female student who was just weeping uncontrollably.”

“There were a number of aspects that made that day – 22 October – particularly horrifying. One, obviously, was the brutality with which riot police responded to unarmed students. Another was the evident terror of the students at finding themselves under fire, and the utter panic which ensued. I remember sheltering from police beside a car next to a female student who was just weeping uncontrollably. And a third was simply the setting: there was something so nightmarish about seeing Parliament, an institution supposed to be serving the people, militarised into a war zone in that manner.”

The #FeesMustFall movement prided itself on being hierarchy-free – which, although a noble concept, actually made reporting on it incredibly challenging. With no defined spokesperson and no one wanting to be seen as leadership of the collective, it not only complicated the coverage from a journalistic perspective but it also diluted the impact as students bounced from one location to another without a real plan in place. Naturally, as a South African protest, the issue of race raised its ugly head too.

Rebecca says: “Some of the students were also extremely hostile to what they perceived as ‘white’ mainstream media, so were forever ordering us to get lost, as much as we tried to argue that it would benefit them to get their demands out there in the press.”

Like a microcosm of State Capture, the lack of leadership resulted in some students using the protests as a vehicle for self-enrichment. “Perhaps the most memorable incident happened to me and Branko outside Parliament on a different day,” Rebecca remembers. “The students had gathered again, and by the time we arrived there was already a commotion because there were suggestions that a student had already been assaulted by police. Students claimed to have video footage of the attack. Branko and I asked if we could use it to verify the incident and we were told that if we wanted to, we would have to pay thousands of rand for the footage. That left us quite gobsmacked because again, we thought it was surely in their interest to get evidence of police brutality out there.”

Putting the opportunistic few aside, Rebecca describes the commitment and bravery of the students as inspiring. She says: “It was an interesting time, and exciting in a lot of ways too. It really felt like South Africa was on the verge of some kind of profound shift: there’s something about young people in particular mobilising in that way that felt important.”

New frontiers

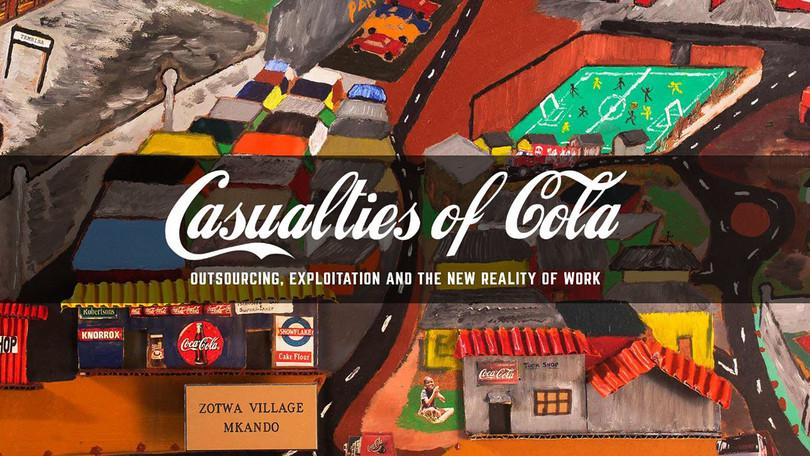

In August 2015, Daily Maverick diversified its offering by partnering with Diana Neille to form Chronicle: a multimedia company. Diana had freelanced previously with Daily Maverick on the mining silicosis feature “Coughing up for Gold”.

The inaugural Daily Maverick Chronicle production was a multimedia feature called “Casualties of Cola: Outsourcing, Exploitation and the New Reality of Work”, which investigated the abuse of South African owner-drivers by the local Coca-Cola distributors, themselves being part of one of the world’s biggest beverage companies, SABMiller. The team behind the project consisted of Poplak, Diana, Shaun Swingler and Sumeya Gasa. With no office yet in sight, the team used Poplak’s house as the war room.

Poplak says: “The idea, I suppose, was to start experimenting with more robust platforms for digital journalism – to start to use the immensely powerful tools we had at our disposal, like video and infographics. I’d long waited to try something like that, and so had Branko, so he paired me up with the Chronicle crew in order to shape their reporting into a coherent story and a coherent look and feel. It was important that it started with the visual and ended with the writing.”

Casualties of Cola went on to win numerous awards, including the CNN Multichoice African Business Journalism Award and a Vodacom Journalism award. It was also first runner-up in the prestigious 2016 Taco Kuiper investigative journalism awards.

Rogues of our Times

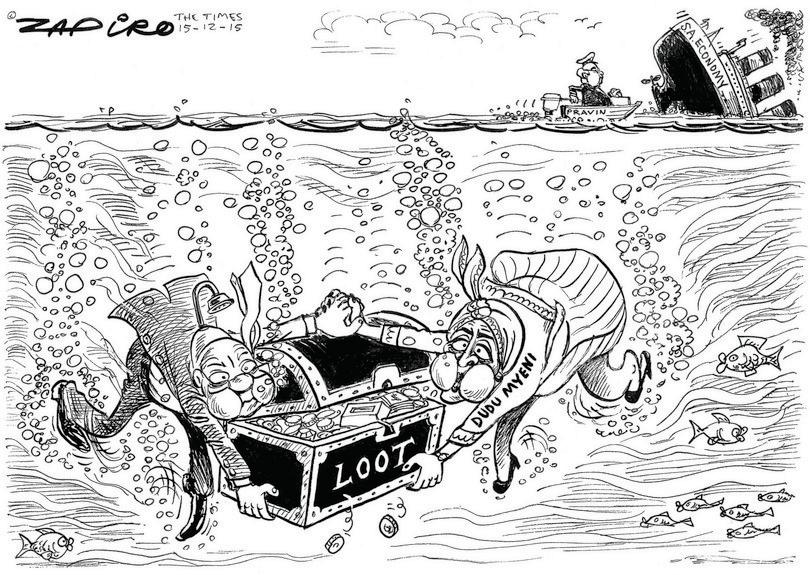

As December 2015 rolled in, two of the biggest stories for Daily Maverick and the country as a whole were set to break, and they were stories that would have repercussions for years. Any thoughts of a normal South African slowdown to the end of the year were well and truly scuppered for the DM team. Marianne Thamm’s exposé of the Sunday Times’ SARS Rogue Unit reports as false – as well as the fake-news circus that mushroomed off the back of that scandal the year before – was the next major national story to cement Daily Maverick as a serious voice.

In her story, headlined “SARS rogue unit controversy: Investigative journalist claims Sunday Times was part of an ‘orchestrated effort’”, Marianne Thamm reported that the “independence of the media has been abused and the Sunday Times had been ‘unethical and immoral’ in its coverage of an alleged covert SARS unit that had been set up to spy on President Jacob Zuma and other ANC members”.

This was according to a former investigative journalist with the paper, Pearlie Joubert, who made the claims in a damning affidavit. Wrote Marianne: “Joubert maintains that the stories published in the paper were false and appeared to have been part of an orchestrated effort to advance untested allegations in public. Her affidavit, unprecedented in post-apartheid South Africa, now places the spotlight on the murky matter of the manipulation of the media to fight bitter political battles.”

Marianne says: “The SARS rogue story crept up on me. I had just finished writing the book, and Branko called me and told me about Pearlie Joubert’s affidavit. I’ve known Pearlie for years so I phoned her and said, ‘What have you done? I’m getting these calls about “affidavit, affidavit, affidavit”, what have you done?’”

Joubert sent Marianne the affidavit in question. “I understood immediately how deeply significant it was; that a journalist who had been part of the investigative team at the Sunday Times was speaking out about her concerns about the way the investigation was being done.”

“I know that I’m committing career suicide but I have to do this.”

The bravery of Pearlie Joubert’s affidavit cannot be overstated. As Marianne explains: “Her affidavit revealed the source, and she said ‘I know that I’m committing career suicide but I have to do this.’ And she did. And not only that, but she then spoke out about editorial meetings where she had raised concerns about the method of investigations, the affidavits that were being brought, the way the investigation had been conducted and that she had problems with how this investigation was being done by the Sunday Times team.”

When Joubert started speaking out against the investigative practices, she was excluded. “I thought that was very interesting because as an investigative journalist myself, I welcome anybody challenging the information I have,” says Marianne. “That’s the way I can get an outsider view. It’s a private safe space. What started happening in this case was that journalists started being cagey about where they were getting their information.”

Marianne’s body of work on SARS would continue the high standard of Daily Maverick’s investigative work, but also package it in her outspoken voice. Marianne never sought to hide her opinions on the matter.

She says: “There comes a time when you realise what you’re dealing with. You read the evidence, the court papers, the affidavits and you draw a line in the sand. I drew a line in the sand when I wrote about apartheid. You can’t be ‘objective’ about apartheid, for God’s sake. It’s a system that had to fall. People were assaulting the revenue service and the Ministry of Finance and it was quite clear why… The people who were working there were trying to do the right thing, they understood their mandate, they were serving the people of South Africa. They weren’t serving a political elite or a political faction, they were doing what they were put there to do.”

Ultimately the Press Ombudsman ruled that the Sunday Times should retract and apologise for 31 stories.

NeneGate

The year’s political and economic low came at the height of December – when President Zuma, without explanation, fired Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene and replaced him with little-known ANC back-bencher Des van Rooyen. This was just the start of “NeneGate”, and all the more shocking as Treasury’s first black African head had delivered a solid performance after only 19 months on a badly listing ship.

Grootes received a call from Branko.

“Zuma’s fired Nene”.

“No, he fucking hasn’t.”

“Yep, he fucking has. Greg is on the business side. Ranjeni is writing up ANC reaction, Poplak is writing an editorial, and you’re ‘Disgusted in Blairgowrie’.” Branko promptly hung up.

Grootes describes it as representing a critical shift in the ANC’s internal dynamics. The statement from ANC Secretary-General Gwede Mantashe on the matter read that the party had “noted the Cabinet change” and that it was “noting that Des van Rooyen had been appointed”.

As Grootes points out, “They didn’t congratulate Van Rooyen. It was a different language and it meant that they hadn’t been consulted. It was the moment where Gwede publicly stepped away from Zuma.”

Daily Maverick’s coverage that night netted 100,000 readers. Grootes says, “We were on it. But we seemed to be the only ones. Business Day were nowhere. They ran Bloomberg copies until 10am.”

In a different sense, however, the timing of the Nene firing was also slightly unfortunate for Daily Maverick. The blockbuster “Casualties of Cola” investigation was launched two days earlier, on 7 December, and the story pretty much owned the country’s national discussion. It was a five-part series and it was being released one-a-day over that whole week. Needless to say, parts four and five were not read as well as the first three.

The Zuma presidency, Poplak’s powerful editorial noted, had reached the point “where self-generated crisis after self-generated crisis has met a commodities meltdown, resulting in something even the most vituperative of Zuma’s detractors couldn’t have predicted: a suicidal kleptocracy so brazen that the president doesn’t bother trying to cover up his true intentions any longer”.

The firing of Nene was, Poplak suggested, “the unthinkable”. The “final insult” after a year of national unrest and insults upon insults.

“President Jacob Zuma has put South Africa’s economy, stability and future at risk by firing respected Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene for reasons he has not bothered to explain. Of course South Africa knows what the reasons are, and they have nothing to do with maintaining the integrity of the Treasury,” reported Ranjeni.

She then listed the damning fallout. “The announcement of Nene’s shock removal from Cabinet sent the rand tumbling on Wednesday. In the context of an international ratings downgrade, poor economic performance and an already battered currency, the move spells disaster for the country.”

In the roller coaster that followed, Grootes brought readers his insights on Zuma’s laughably insufficient statements on the matter.

“President Jacob Zuma has never been one to give the commercial middle-class media much time. And he has never felt the need to explain himself in public much either. Once, he even put out a statement saying that when it came to cabinet re-shuffles, he didn’t have to explain his decisions. So it must be an indication of how the pressure is beginning to have an impact that over the weekend he released a series of statements, all relating to the sacking of Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene,” wrote Grootes.

It was pretty inevitable that Nene’s inexperienced replacement, Des van Rooyen, would get the boot sooner rather than later. Not even Grootes anticipated just how soon, though. After a frantic week, he had turned his phone to power-saving mode on Sunday night so the constant ding of the Carpe DM messages would be silenced. He was still able to receive calls; and as he was about to switch off completely for the night, the phone rang. It was Branko.

“Pravin is the Minister of Finance.”

“Fuck off, no he’s not.”

“He is, turn on your fucking messages.”

“The guy could just laugh. Not in a menacing way. He was laughing because he couldn’t believe how crazy this was either.”

Not quite able to believe the statement he was reading, Grootes phoned an official at the Presidency to check that it was, in fact, true. “I asked, ‘Is this legit?’ The guy could just laugh. Not in a menacing way. He was laughing because he couldn’t believe how crazy this was either. ‘Yes, it’s legit.’”

Marianne’s “Game of thrones, Pravin Gordhan edition: When the target reclaims the hot-seat by default” delivered the full and farcical plot twists as Gordhan was called in to take over from Van Rooyen. “It is a supreme but delicious irony that the old new Minister of Finance, Pravin Gordhan, will now be the person dealing with a compromised KPMG report, commissioned by SARS to look into a so-called ‘rogue unit’ allegedly established under his watch as commissioner of the revenue service. President Jacob Zuma’s hubristic move in firing Nhlanhla Nene last week – triggering a tailspin for the rand – left No 1 with no option but to surrender the public purse back to Gordhan, and in so doing score a spectacular own goal. Let the games begin.”

If any story was indicative of the public mood, it came, among a string of NeneGate stories on the Daily Maverick website, in the form of Deputy EFF President Floyd Shivambu’s “South Africa is under the management of the Guptas”, one of the year’s most popular opinionista pieces.

“We should never agree, as this generation have, to be puppet-mastered as if there are no rules and principles that govern this country. We call on all South Africans to stand up against the Gupta syndicate because we will soon be left with no country,” Shivambu urged. “Now that their National Treasury capture has failed, they will resort to other means of looting. They still control the majority faction in the ANC, and they have already said who their person of the year is through some bogus awards ceremony. We should not be afraid, we should fight to decolonise South Africa from Guptas.”

Rebecca departs

With no office and the constant threat of “Will Daily Maverick survive another month?” looming overhead like a posse of Harry Potter dementors, Rebecca decided to jump ship at the end of 2015. She says: “I thought it was maybe time to experience a news outlet that had an actual physical newsroom: at the point when I left, DM had no offices, fewer writers and I was feeling increasingly isolated.”

It’s often difficult to leave a job, but the extremely close-knit Daily Maverick culture, which quickly turned colleagues into real friends, made it particularly heart-wrenching for Rebecca.

“I asked Styli to meet me at a Sea Point café and told him I was leaving. I just bawled,” she says. “Poor guy.”

Losing Rebecca spurred Styli and Branko to understand that “putting editorial first” also meant ensuring their working environment could support their writing efforts.

The R12m penis pic

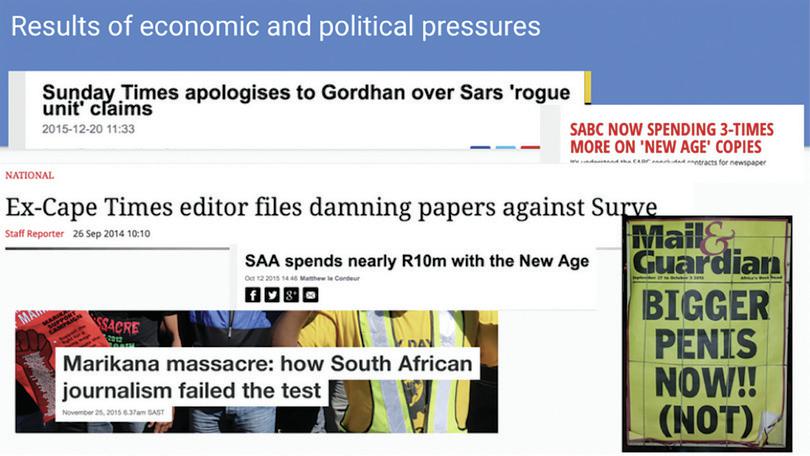

2015 was not a positive year for South African press freedom, with the signal-jamming episode at SONA a sinister indication of just how far Zuma was willing to go in his attempt to control the narrative. It was also a bad year for journalism, with the Sunday Times casting the profession in a distinctly negative light with its Rogue Unit collusion. But, as we know, what’s bad for the country can be good for business. The bad press of the bad press had allowed Daily Maverick to stumble into good lighting. Finally the ethos of always putting editorial first was about to pay off.

And it all started two years previously – with a penis pic.

Styli recalls, “It was Thursday 27 September 2013. I know because the timestamp is in the picture, and it was the day before the Mail & Guardian hit the stores and streets, so it must have been a Thursday.”

Styli was still living in Johannesburg at the time. Driving home that evening along the busy William Nicol Drive, his eye was caught by a bright yellow street poster: the mechanism used by newspapers to advertise their next issue. This one particularly grabbed his attention.

“Bigger Penis (Now)!! Not” it screamed. While tabloids have made use of street posters like this since time immemorial, this poster was advertising a highly reputable publication – the Mail & Guardian. (It emerged that the poster was in reference to an article in that week’s edition about the sale of muti to enhance penis size.)

“This was the Mail & Guardian, for goodness sake!” marvels Styli. “I pulled over on the side of the road and dodged the legal and financial cowboys racing out of the Sandton CBD to take the snap. I must have looked a fool taking a photo of a street poster on the middle island of a charging road.”

To Styli, the poster was a perfect metaphor for the decline of South African journalism. “After sharing it with Branko, and the five-minute ‘what the…’ conversation that followed, I felt a sense of genuine anger overcome me. This is what journalism had become, had to resort to in order to stay relevant. The impact of digital clickbait journalism had now infiltrated one of South Africa’s most revered print publications. Despite revelling in the obvious long-term benefits it would have for Daily Maverick, it made me sad to think that this is how low journalism had sunk. In a time when the country needed it most.”

That poster, he says, became “the fuel to remind me that what we were doing was even more important. That we could not yield to chasing popularity or page-views over the important stories that needed to be told.” It’s a principle neither Styli nor Branko has ever wavered from.

But Styli says his picture of the street poster was to serve another, more practical purpose – one that would help them raise a further R12-million for Daily Maverick, two years later.

“One of the impact slides in my pitch deck in 2015 covered the meltdown happening in the SA media landscape, and why investing in Daily Maverick was about more than just a financial return – and whether we could afford not to keep the DM flame burning. Headlines like ‘SAA spends nearly R10m with The New Age’ and ‘How SA journalism failed in coverage of Marikana’ filled the slide. But the most prominent, yellow, bulging image was the photo of that M&G street poster, now known as the penis pic that helped us raise R12-million.”

R12-million was more than Daily Maverick had ever raised before. It was the lifeboat the team needed. It meant they could rent an office. It meant new recruits. It meant they could keep their eye on the ball. It meant that quality journalism would survive another day. And for possibly the first time since launching, Styli and Branko could breathe a sigh of relief. For now.