The age of Zuma

Almost exactly six months before the Daily Maverick website went live, president Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma had taken office. And hard as it may be to believe from the vantage point of 2019 – as South Africa continues to crawl, badly wounded, from the quagmire of State Capture – there was initially a sense of optimism around the Zuma presidency.

That’s despite the fact that Zuma had already faced two different sets of criminal charges, having stood trial for the rape of Fezekile “Khwezi” Kuzwayo in 2006 – and been controversially acquitted – and having had charges of corruption linked to the notorious Arms Deal dropped against him in 2008 due to alleged political interference.

Before he took office, it had already been clear for some time that even exceptionally serious allegations of misconduct were unlikely to prevent Zuma’s ascent to the Union Buildings.

Branko says: “The first time I realised something was happening around Zuma was when he was fired by Thabo Mbeki [under suspicion of what would later become the corruption charges] in 2005. We had Zuma on the cover of Maverick magazine in 2007, with an interview with him. The story was basically about him not saying anything – but he was very, very self-confident.”

The Maverick cover strapline read: “Zumocracy”. It was published six months before the ANC’s electoral conference in Polokwane.

“He was the deputy president of the ANC at the time, he had been fired as deputy president of the country, he had just survived rape charges and we said, ‘Zuma will be next president of South Africa’,” says Branko. “We were the first ones to call it.”

They were right. While 700 journalists from all over the world looked on, and as “Polokwane” became the most searched term on Google News for probably the first and last time in history, Zuma came out on top. With the backing of Cosatu, the SACP, ANCYL, ANCWL and five of the nine provinces, Zuma swept to victory; not only dislodging Mbeki as president of the ANC, but also placing loyalists throughout the ANC’s Top Six.

TV news footage showed Zuma’s supporters rolling one hand over the other: the sign used in soccer games to indicate that a substitution was needed. The signal was clear: they wanted change and the man they believed would bring it was Zuma.

At the time, you did not have to identify as “100% for Zuma” – as supporters’ T-shirts proclaimed – to also want change. Sentiment had turned against Mbeki, who had originally seemed to promise so much as Nelson Mandela’s successor. Most questionable among all Mbeki’s policy decisions was his senseless obstructionism towards South Africa’s HIV/Aids antiretroviral programme.

No matter how much the burning rubbish dump of Zuma’s presidency may put a gloss on Mbeki’s almost two-term tenure, he will always be seen as complicit in the unnecessary deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. Others have been tried for genocide for less.

At Maverick magazine, opinion was divided as to whether Zuma could really be that bad in comparison.

Branko says: “Phillip and Kevin disagreed with me. After Polokwane, they drank a bit of the Kool-Aid, because lots of people were happy that Mbeki was out. They were saying that Zuma being in charge was not all bad. I said, no, this is a disaster.”

Kevin asked at the time, in his reporter’s notes covering the Polokwane conference: “How bad can a Zuma victory be, if it brings a new NEC and therefore a new government executive?”

It was almost as if Fate was listening, snorted, got up from the couch and said, “Hold my beer.”

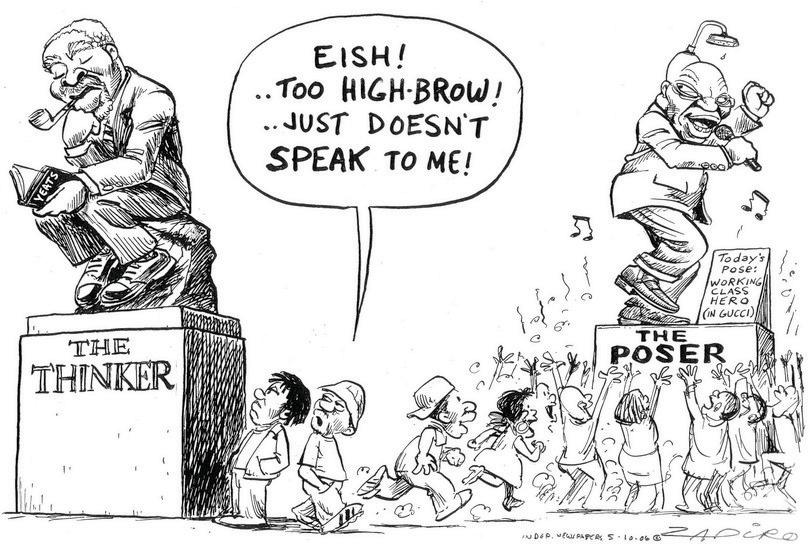

But at the start of 2010, less than a year into the Zuma presidency, there was still one politician getting more attention than anybody else.

Bad Juju

In “The year ahead in politics: Julius Malema”, Stephen Grootes predicted that “there’s probably no way under heaven for the newsmaker of 2009 to create any more attention for himself” – but not overlooking the not-so-trifling aside that “he doesn’t have the self-control to keep quiet. And thus he is likely to sound, well, like an idiot again several times this year”. Grootes wasn’t wrong.

Some nine years before Julius Malema would unleash journalist Karima Brown’s phone number on Twitter, and his EFF supporters would threaten her on WhatsApp with rape and violence by skin peeling, Daily Maverick reported on the firebrand’s makings as hate speaker and harasser of women, after “the Johannesburg Equality Court ruled that Julius Malema is guilty of hate speech, has no protection in terms of freedom of speech provisions, denigrated women in general, added to the rape problem in South Africa, and must apologise”, writes Phillip.

That was March 2010. Malema had been taken to the Equality Court after comments he made while addressing students at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) in January 2009. During his speech, Malema cast aspersions on the conduct of Zuma’s rape accuser after the alleged rape, saying: “When a woman didn’t enjoy it, she leaves early in the morning. Those who had a nice time will wait until the sun comes out, request breakfast and ask for taxi money.”

Of course, it would take Malema some 15 months to heed the Equality Court’s order to apologise for his comments and pay a R50,000 fine to People Opposed to Women Abuse.

When launching his own political party, Malema would attempt to rebrand himself as a feminist figurehead. But to those acquainted with his behaviour from the ANC Youth League days, what he had displayed most prominently was a basic disregard for the violence of a machismo culture.

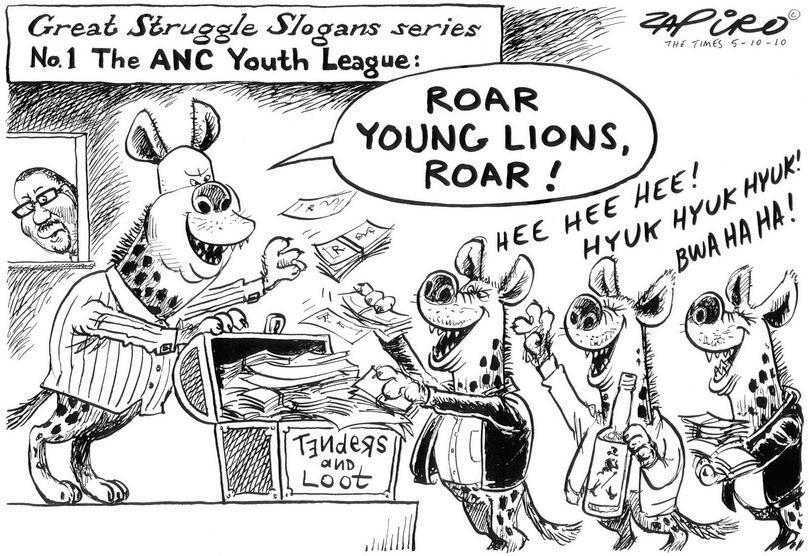

Back in 2010, Daily Maverick continued to report on every aspect of the rise and rise of Juju. The titanic rift between Malema and President Zuma, pitting the “young lions” against the old guard; his ANC disciplinary review, in which he was fined R10,000 and ordered to attend anger management classes; and some of Malema’s biggest mistakes.

“The big talker who fails to deliver,” Daily Maverick writer Sipho Hlongwane called him, for the ANC youth wing’s failure to make good on their promises to send shoes and wheelchairs to needy schools.

In December, Phillip turned the spotlight on Malema’s latest campaign to push through the ANCYL’s pet projects – including the nationalisation of mines – at the ANC national general council meeting in September. But Phillip revealed just how little headway Malema had made.

“He pulled off an award-winning performance of ease and relaxation, saying the ANC Youth League had won ground in every area except one (the matter of his suspended disciplinary sentence),” wrote Phillip.

“From where we’re standing, it looks awfully like the Youth League had its push for the nationalisation of mines sandbagged, its efforts to install Fikile Mbalula as its man on the ANC’s Top Six torpedoed and its determination to have Malema’s suspended party sentence (from the last time he tangled with Jacob Zuma) reversed.”

Should the media be giving so much airtime to a loose cannon seemingly only emboldened by undeserved attention?

Branko’s answer: Hell yes!”

Given Malema’s pretty poor record when it came to actually influencing ANC policy, by the end of 2010 Branko was already raising a question that would come to be asked roughly a billion times over the course of the next nine years. That was: should the media be giving so much airtime to a loose cannon seemingly only emboldened by undeserved attention?

Branko’s answer: Hell yes! In his analysis, the Daily Maverick editor gave multiple reasons to keep the centre-stage spotlight trained firmly on Juju’s shenanigans.

“If unchecked by the media, Julius Malema could eventually go on to become a real-life ruler of the ANC and South Africa. If left to do whatever he pleases, protected in anonymity by the media’s self-imposed silence, he could have arranged to win every tender imaginable, replace every ANC official he doesn’t like, nationalise this country’s mineral wealth and who knows what more,” he wrote.

“If he were to continue untouched, we could have South Africa’s close alliance with Zanu-PF and other exemplary friends that would probably make us think back with nostalgia on the times we shouted against Mbeki and hurled insults at Zuma. By that time though, no decent and self-respecting country would even touch South Africa.”

Branko knew that, as long “there are still people who care, we need to shout the truth about Julius Malema, or anyone else”. In the years to come, Daily Maverick would do just that, “loudly and as often as it could”.

The Gathering

2010 gave birth to another of Branko’s dreams: to establish something along the lines of a South African version of TED Talks, only with less smugness and more robust debate.

The name The Gathering, while appropriate for a get-together of some of South Africa’s biggest newsmakers and most influential talking heads, actually comes from Branko’s affinity for science fiction. Remember the Highlander film? Lots of immortal chaps with swords meet up at something called “The Gathering” and try to chop off each other’s heads so they can get juiced up by magic murder lightning.

Thus far there haven’t been any decapitations at Daily Maverick’s Gatherings, but there has been verbal bloodshed aplenty as political arch‑enemies have duked it out on stage.

November 2010 saw the inaugural The Gathering take over Joburg’s Sandton Theatre on the Square. Ticket pricing was pegged to the developing speakers’ roster. Branko explains: “Every couple of days we would gain more speakers and the price would go up again. We had 16 speakers at the first one. It was beautiful.”

The audience was small – 200 people; no visible swords – but enthusiasm ran high. The idea was simple: get interesting people from a wide variety of different spaces to talk about their passion. Then-FNB CEO Michael Jordaan, for instance, spoke about the dangers of following the law of averages.

“It was a cool approach, as opposed to him coming and talking about banking,” Styli says. Despite Daily Maverick’s infancy, Branko’s personal network meant that speakers other than Jordaan included erstwhile Sunday Times editor Ray Hartley, former Cosatu General Secretary Zwelinzima Vavi, and his ANC counterpart of the time Gwede Mantashe.

“There was just a podium and a microphone. That was it. The SABC rocked up on the day because Gwede and Zweli were talking. I remember walking up onto the stage and putting gaffer tape down onto the microphone – it was that kind of raw operation. We didn’t know any better,” says Styli.

And also in 2010…

Only obsessive politics nerds (in other words, most of Daily Maverick’s staff) associate 2010 in South Africa with events within the always turbulent body politic. For normal people, the year remains synonymous with one thing only: the Soccer World Cup, now often recalled with misty-eyed nostalgia as one of the last occasions on which the country felt caught up in the grip of unity and patriotism.

Just one problem: Daily Maverick was netting only 2,000-3,000 readers a day, and the editorial team was plugging ahead on budgets thinner than footballers’ shoelaces. Setting the tone for a publication where staff have always had to pitch in wherever needed, Branko himself wrote 38 of the 54 stories the Mavericks produced during the World Cup.

Dominating global headlines that same year were the revelations of WikiLeaks. Spearheaded by Australian info-guerrilla Julian Assange, the WikiLeaks narrative gave the world in 2010 an anti-authoritarian streak that chimed with the heart of Daily Maverick’s counter-culture approach.

Sipho Hlongwane brought readers several refreshing angles on the story everyone was talking about. Sipho ticked all WikiLeaks’ biggest moments – from the release of a flood of confidential US diplomatic cables to leaking hitherto secret aspects of the Iraq war and blowing apart US military cover-ups in Afghanistan. But Daily Maverick also got stuck into the South African implications of the whistle-blower organisation’s contrarian onslaught against the US government in particular.

Some of the leaked US cables dealt with South African presidents Jacob Zuma and Thabo Mbeki – and the ubiquitous Malema came in for a (dis)honourable mention.

Columnist Ivo Vegter, ever taking the counterintuitive approach, predicted: “One day, we’ll all hate WikiLeaks.” Vegter suggested that a distinction should be drawn between whistle-blowing and a stadium full of vuvuzelas. “One can be ethically questionable but ultimately moral; the other is overbearing noise that initially makes us smile, but ultimately makes us all deaf,” he wrote.

At that stage, there was no way of predicting just how vital whistle-blowers would become to saving a country on the brink of catastrophe some seven years later.