Annus horribilis

“We were scrounging every flipping cent,” Branko remembers. “It affected us badly. I was sick. For eight months I took a fistful of steroids, every day. You can imagine what that does to you. Thankfully I responded well to the drugs. While being sick did not affect my ability to work, it did affect my ability to communicate with my people.”

For Styli, the crippling cash-flow problems had him ready to throw in the towel. “We’d run out of money. Again. I was expected to ask shareholders for more money. Again. I was tired, deflated, broke, and my wife was fed up with me. I told Branko to ask for the money because I was done asking.”

The Daily Maverick shareholders came through, understanding that their investment had become less about the prospects of profit and was effectively a donation to a company, and a vision, they believed in. But even with this vote of confidence, the constant struggle to stay afloat was beginning to take a serious toll on both Branko and Styli.

Branko reflects: “You think about failure all the time – there’s a good chance this thing is not going to work. But if you let that consume you, it will not work. What both Styli and I have is that we are impossibly stubborn. I gave up on Maverick magazine because there was literally no way out. I tried everything in my power. With Daily Maverick, for as long as I am alive, this thing is going to live. What has always been incredibly important is that we are not afraid to do things. We are not afraid to try.”

But that didn’t mean their mission didn’t sometimes feel downright foolish. Says Styli: “Starting out as digital-only, covering politics in the Zuma era, and facing off against Google and Facebook for ad spend is probably the dumbest thing that anyone can do. We just didn’t know it at the time.”

A political monster is born

Embracing the lack of Daily Maverick offices, Poplak took himself on the road to report on the campaign trail leading up to the year’s general elections. The nom de plume he adopted for this mission: Hannibal Elector. The name was appropriate for the savaging Poplak would proceed to inflict on South Africa’s political hopefuls. First in the firing line was Helen Zille, erstwhile leader of the Democratic Alliance.

Strangely – or perhaps not so strangely – every time I encounter Helen Zille in a room, my mind flashes to a Braveheart-style montage: the Democratic Alliance’s stalwart leader, head shaved, face smeared with blood and war paint, guiding 10,000 troops forward into battle. It’s just a flash, but it happens every time, and it makes me a little scared and uncomfortable – this sense that if Zille ever did become president of this country, a role she most certainly covets, I would be conscripted into service for the invasion of Zimbabwe or Mozambique or some other nearby candidate for regime change, urged to war by the howling President herself.

I can’t figure out if this is just a boilerplate Freudian reaction to a Strong Woman, a mother figure who is uncompromising and ambitious and cunning, and whom could have my balls for Sunday lunch hors d’oeuvres before I realised they were missing. But I don’t feel that way about all Strong Women – Lindiwe Mazibuko was sitting two chairs down from Zille, and I received zero Braveheart vibes from her. No, some people are born warriors, genetically predisposed to consuming the livers of their vanquished enemies amid the gore of a war zone.

Helen Zille is one such person.

Poplak went on to question the algorithm that appeared to lie behind the DA’s chosen electoral candidates:

The list of the DA’s Chosen Ones seemed perfectly calibrated to reflect Diversity, as if the pigment of all of the candidates had been run through a software program designed to identify the Platonic ideal of racial rainbow-ism, and reflect that ideal back to South African voters.

Whomever you may be, stated the candidates wordlessly, we have your flavour.

When my colleague Ranjeni Munusamy, clearly thinking along the same lines, asked Ms Zille during question period whether the candidates were chosen by a strict racial quota inspired by a Coke commercial, I got my most powerful Braveheart flash yet. Zille swallowed and looked hard at Munusamy, in a way that suggested that should Zille ever occupy State House, Munusamy would be one of the first – but not the very first – to be dumped down an active Karoo fracking hole. Meanwhile, at mention of the word “race”, the DA candidates’ eyes widened in abject alarm, as if a locomotive had crashed into the room, followed shortly by a 747.

“We believe in excellence and equity,” said Zille slowly, “and those two are not contradictory.” Munusamy did something with her iPad, presumably to do with hiring a security contingent.

And so went one of the first instalments of Hannibal Elector’s coverage. Unsurprisingly, the DA didn’t like it. In fact, Zille went as far as to commission research into Poplak’s history. Upon discovering that he left South Africa for the politically starched slopes of Canada in 1989, Zille fired off a series of tweets questioning Poplak’s character for abandoning South Africa during its time of greatest need. One problem: Poplak was 15 years old in 1989, and thus not fully in control of his family’s decision to uproot.

Unperturbed by unleashing the fury of the Zille-warrior, Hannibal Elector continued to let rip. Doing so was irresistible in a year when the DA was serving up some spectacular nuggets of political faux pas. The ill-fated marriage of the DA and new political party Agang; the kiss of death between Zille and Agang’s leader Mamphela Ramphele; the swift and acrimonious divorce; the comical confusion around a march on Luthuli House … and all this before March.

Meanwhile, in the world of more serious politics, Public Protector Thuli Madonsela was sharpening her own spear for a Nkandla-sized knockout.

Nkandla knockout

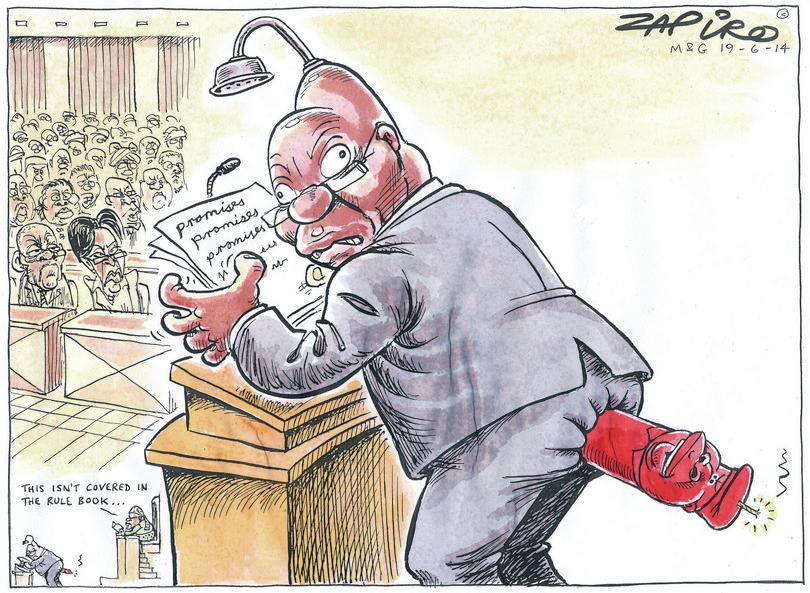

In March 2014, Madonsela found that portions of the R246-million taxpayer-funded refurbishments at President Jacob Zuma’s Nkandla residence were unlawful, and ordered him to repay part of the cost.

“The Public Protector’s office has found President Jacob Zuma guilty of ethical violations regarding the security upgrades to his Nkandla homestead. As the report notes, ‘[Zuma’s] failure to act in protection of state resources constitutes a violation of the executive ethics code’,” wrote Ranjeni Munusamy and Richard Poplak.

“This, Madonsela says, ‘is inconsistent with his office as a member of Cabinet, as contemplated by section 96 of the Constitution’.” The writers call it “a devastating report of a Presidency gone awry”.

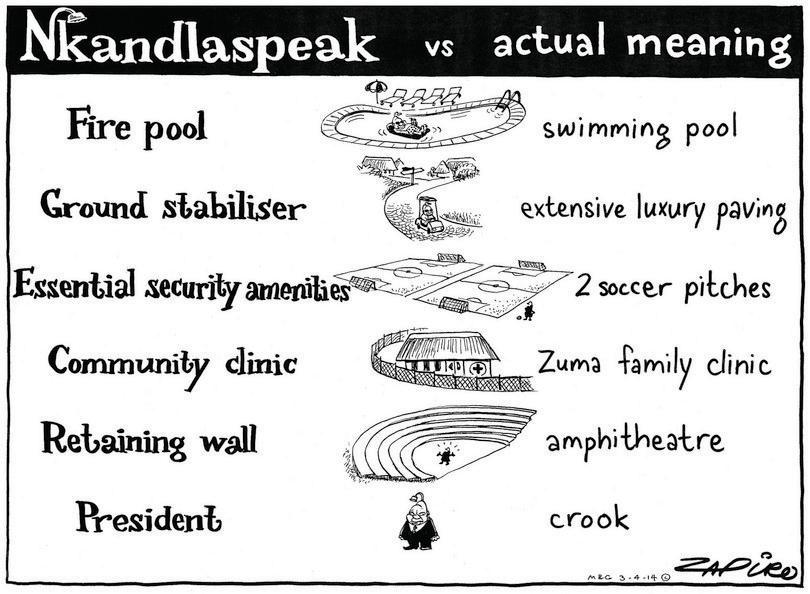

Quoting the report in an accompanying piece, Poplak instructs the reader, “Scheme this: ‘It has already been indicated that no specific documents were provided that expressly authorise the building of a clinic.’ Or this: ‘It is obvious that the state has made a major contribution to the President’s estate at the expense of the taxpayer.’ Or this: ‘Clearly, items such as the Visitor’s Centre, swimming pool and terrace, amphitheatre, elaborate paved roads, terraces and walkways and the building of the kraal, with an aesthetically pleasing structure, a culvert with a remote-controlled gate and chicken run, added substantial value to the property.’ Chickens wielding remote controls? Yes, South Africans, welcome to Nkandla.”

Despite the ANC’s best efforts, the Nkandla scandal didn’t go away, although they did manage to kick the can far enough down the road to emerge from the elections relatively unscathed. As any ostrich would tell you if they could, sticking your head in the sand doesn’t make the problem go away. Ranjeni expanded on this in “The ANC’s big fat Nkandla migraine”:

“The ANC and President Jacob Zuma probably thought that deferring the matter until the establishment of the new Parliament would neutralise it somewhat.

How wrong they were.

Opposition parties are determined to deal with the matter extensively, to ensure that Madonsela’s recommendations are implemented fully – including that Zuma pay back money to the state for undue benefits he received – and that the president be made to account for his role and knowledge of the upgrades. Had the matter been dealt with in the last term, it probably would have caused some discomfort and embarrassment for Zuma, and had repercussions for the ANC. But there would have been a finite timeline to deal with it, and if Zuma had given the cursory impression that he was implementing some of Madonsela’s recommendations, it would have taken the sting out of the issue.”

Nkandla might have been a nightmare for Zuma and his party. But for one opposition party, it presented an equally monumental opportunity – to create one of the biggest dramas ever to unfold in South Africa’s democratic Parliament.

And the Oscar goes to…

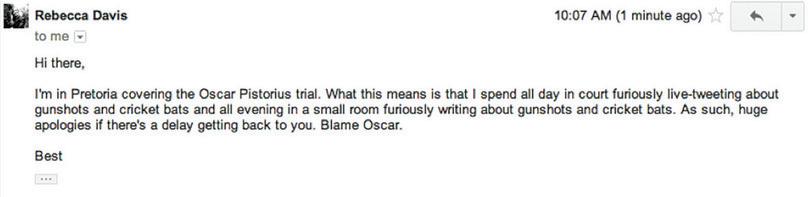

Rebecca Davis! Having won the completely uncontested position of official Daily Maverick reporter on the Oscar Pistorius story on Valentine’s Day 2013, Rebecca would be tasked with bringing the latest on Pistorius’ murder trial to readers well into 2014.

She now describes her coverage of the Pistorius trial as “both a career lowlight and highlight. It was a lowlight because of the essential tabloid-ism of the subject matter – sports star kills girlfriend – and because of how hard I had to work to find angles on the story, like gun crime and violence against women, to justify our focus on it in a country where so many women who are not rich, white and famous are murdered by their not rich, not white and not famous partners. It was also a lowlight because of how much I hated living in Pretoria for the duration of the story. But candidly speaking, I suppose I have to say it was also a highlight because live-tweeting that trial seriously raised my profile.”

To describe what her daily existence had become, Rebecca put it most succinctly in her out-of-office email reply at the time:

The trial ran for six months, and while her colleagues were embroiled in the general election coverage, Davis was navigating the wet streets of Pretoria, dealing with the journalistic politics of courtroom-assigned seating.

“My hotel was 3km from the North Gauteng High Court, and I had to walk to and from the courtroom every day. It rained, torrentially, almost daily. As I walked the roads of central Pretoria, large cars would swoosh by and, due to the poor street drainage systems, they would drench me from head to toe. I would stand, sodden, wiping water from my face like the nerd in a high-school movie. When this happened, I would shake my fist at the sky and mouth: Fuck you, Oscar.”

Many South Africans were morbidly fascinated by the so-called “trial of the century”, and tuned in daily to watch our very own OJ Simpson-esque courtroom drama unfold. Rebecca says that the television coverage didn’t quite match the experience of sitting in that courtroom.

“Because of the hundreds of journalists frantically typing away in the courtroom, and the fact that most witnesses in the trial were intimidated as hell and spoke really softly, we often couldn’t hear the testimony as well as people watching at home. On the other hand, there were aspects of being present in the courtroom that you couldn’t easily replicate at home: primarily, the sight and sound of Pistorius vomiting into a green bucket at a particularly gory moment of testimony. I was seriously grateful I’d chosen a seat on the other side of the courtroom, because if I’d been any closer I might have started sympathy-retching in response.”

Davis’ position in the courtroom was in itself part of a strange setup. “There was a weird kind of politics involved in the journalists’ seating in the courtroom, whereby reporters from Afrikaans publications tended to sit directly behind the Pistorius family, and English-medium reporters (like me) chose the other side behind Team Steenkamp. I’m not saying this was reflected in the consequent reporting, but I do remember some Afrikaans journalists being put under pressure by the Pistorius family to sit closer to them, in the apparent hope of building an alliance.”

Despite being one of the most sensational spectacles in South African news in decades, the trial inevitably took its toll on everyone involved – journalists included. They couldn’t, like the rest of the country, switch it off when it became too harrowing or, frankly, too boring. Day in and day out, they filed into court to hear the testimony surrounding the tragic end of a woman made famous by the manner of her death – all the while being guiltily aware of the country’s ongoing torrent of other forms of brutality being neglected as a result of the all-consuming Pistorius focus.

At times, the violence extended outside the trial’s walls. Rebecca remembers: “There was a slight hint of danger on the mean streets of Pretoria; a fellow journalist had his cellphone taken off him at knifepoint a few roads from the courthouse. On one memorable morning, I was chased for the best part of 3km by a madman screaming at me to give him my phone or he would shoot me. At this stage I’d been covering the Pistorius trial for long enough to believe that the Jacaranda City was as awash with weaponry as a Brazilian favela: the elderly tannie who ran a café near the courthouse had previously shown me the revolver she kept tucked into the elasticated waistband of her pants. I made it to court safely in the end because my would-be assailant proved too mad to run and shout things at the same time over long distances.”

Other Mavericks jumped on the beat from time to time too, with Ranjeni producing one of Daily Maverick’s most-read pieces of the year.

“On Thursday afternoon, after the Oscar Pistorius trial adjourned in the North Gauteng High Court, the athlete’s brother Carl Pistorius tweeted: ‘If you lie with dogs, you get fleas – Anon’. That could possibly explain the prickly, itching sensation South Africa feels after being exposed to the Oscar Pistorius contagion for 18 months, through 47 court days,” Ranjeni wrote, summing up the general exasperation most South Africans felt at that moment.

“All of it, the drama, the tragedy, the showmanship, his spectacular fall from grace, the gallantry of carrying and crying over a bloodied corpse, the fake devastation, showed how he is better than the rest of us. The conclusion of the sentencing procedure is probably not the last we will hear of and see our champ as an appeals process is sure to ensue. He will continue to contaminate and assault the national consciousness with his charmed existence.”

Less than a week later, presiding Judge Thokozile Masipa would sentence Oscar “Bladerunner” Pistorius to a maximum of five years for the crime of culpable homicide.

As ever, this was a story where Daily Maverick tried to offer alternative perspectives to the standard press line. Greg netted a photo of Pistorius as he entered the courtroom. Rather than squeezing himself into the mob of photographers all laying claim to the accused from the same angle in the press gallery, Greg had staked out a different corner of the court, depicting the full story – the fallen Icarus being devoured by the very press corps who had helped mythologise him.

As for Davis? She found she couldn’t escape Pistorius. In 2014, the African Media Initiative was awarding grants for health stories. Rebecca pitched an investigation into the plight of former South African miners who contracted lung disease, and was given a grant to develop it into a multimedia project. The resulting feature, “Coughing up for Gold” would become the catalyst for Daily Maverick’s entry into the terrain of multimedia – and won Davis the continent-wide African Story Challenge award.

Her prize: to spend a month gaining experience at any newsroom in the world. She chose The Guardian, in London, for the month of October 2014.

“What a delight to flee from South African news for a few weeks and get a wider perspective! Except that, during the precise period while I was there, the sentencing of Pistorius happened. And my editors at The Guardian put me straight on it. So I ended up sitting at The Guardian, live-blogging the sentencing of Oscar Pistorius, silently cursing him once again.”

The EFFing election

To watch the elections unfold as part of his Hannibal Elector series, Poplak travelled from Marikana to Bekkersdal to a township in Springs. “Democracy is a funny thing, especially when the army has been called in to enforce it,” came his wry observation.

Invoking the ANC’s hoary election slogan, Poplak wrote: “There are many Good Stories to Tell in this country. But on my own 24-hour road trip, there were very few. In a country edging towards the edge, where democracy already feels like a failed project in so many communities, violence seems like a lingua franca, and voting seems absurd. It’s a strange thing to acknowledge after covering an election for four-and-a-half months, and even stranger to acknowledge in a country that almost killed itself to acquire these rights.”

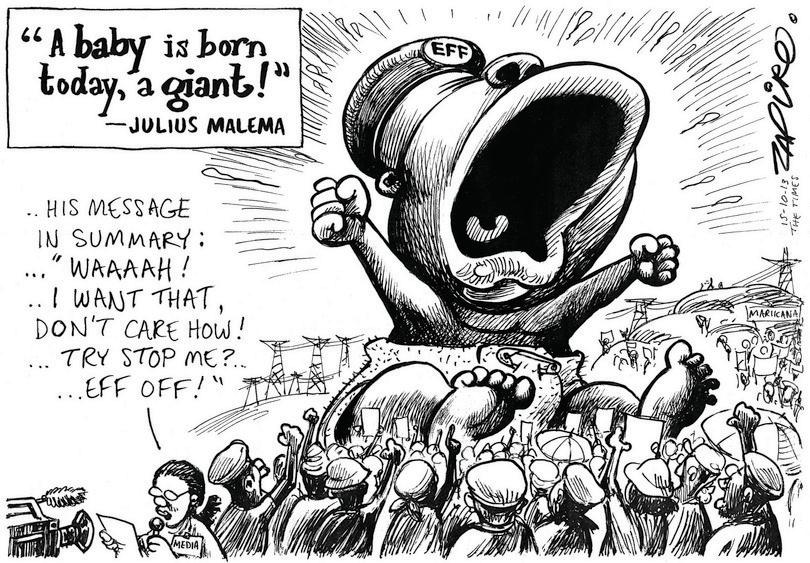

Leaning in to speak to Richard at an EFF rally in Marikana, Malema promised him: “I will win.”

Which begged the question: “How can he lose? But in the big white men with big guns who ushered him into the car, I saw the echoes of the previous guys who ran the show – echoes I saw across Gauteng for the length of this campaign, echoes that are even starker on election day. If 20 years ago you’d told me that a Grade 4 student would be arrested for throwing petrol bombs at cops the night before the fifth national elections, I’d have called you crazy.”

It was easy to laugh at Malema’s presidential ambitions – in much the same way that South Africa would titter at Hlaudi Motsoeneng’s, some five years later, when the disgraced SABC boss would refer to himself in the third person as the country’s tzar-in-waiting. But Malema was deadly earnest. Someone who knew that from the beginning was Poplak.

“If you are a politics junkie, it’s not very often that you get to see and chart the rise of what I believed would be a truly seismic political movement.”

He says: “I always took him seriously. We always felt that way, me and Branko, to varying degrees, and I wanted to get in there as early as I could when they formulated the party, to try to track this phenomenon. If you are a politics junkie, it’s not very often that you get to see and chart the rise of what I believed would be a truly seismic political movement. How often do you get to do that? Maybe once in your career if you’re lucky. The second is that I understood Julius as a political savant, almost like the LeBron James of politics. We had never really had that here. We had someone like Zuma who could work the back rooms of the ANC, but never a guy who was both front of house and back of house simultaneously and who could do pretty much everything, who had an incredibly in-depth knowledge of parliamentary processes, of precedence, of how committees work. Just a complete political creature who understood the system to a T and who was also a populist. So, for me, it was incredible and I am very, very grateful for the experience.”

To overcome public scepticism around their credibility as just another ANC offshoot, the EFF set about doing things differently. For starters, its leaders rebranded who they were. No more obvious bling. No more high-flying lifestyle: at least, not in public, not for a while. Instead, when the Fighters entered Parliament after the 2014 elections, they did so wearing the uniform of the working class: overalls, maids’ outfits and miners’ hard hats. To that they added a slight martial touch with berets and the nomenclature of the armed forces. Malema, of course, made himself Commander-in-Chief. It was an obvious form of political pageantry, but a canny one – because it suggested a sharp break from politics as normal.

And the media lapped it up. Politicians from the DA, which would substantially outperform the EFF in that and every subsequent election, would often complain that journalists jumped to attention when Malema so much as snapped his fingers.

Poplak says: “It’s one of the pathetic things about how media works. We have this symbiotic relationship with these populists. I would argue that the work we did on the EFF, me and Branko specifically, was necessary. It’s so easy to call them a media creation, but at the same time, much of what Malema was saying, white northern suburbs people were agreeing with last year exactly at this point. So fuck you. I get that symbiosis, but that is not purely a creation of the media, it’s also due to the demand from the market, our consumers, whatever you want to call them – to be scared. We know we should be scared. We know there should be disruption. We know that there should be revolution. We know it! We can’t pretend. The symbiosis is queasy, it troubles me, but at the same time I have zero regrets about the work that we did and the manner in which we did it.”

Election day arrived on 7 May and despite a first term already plagued by controversy, the Zuma and the ANC won a convincing 62.1% majority, although down from 65.9% in the 2009 elections. The DA increased their margin from 16.7% to 22.2%, capitalising on the drama of the previous four years but not sufficiently to make any real headway. As for the EFF, the underdogs walked away with 6.4% of the vote, including more than 10% in Gauteng, Limpopo and the North West. It was enough to net them 25 seats in the National Assembly. Enough to ensure that Parliament would never be the same again.

In his final contribution as Hannibal Elector for the 2014 elections, Poplak summed up what his vision of real democracy would look like, one that would continue long after the voting booths had closed.

“It’s a politics that South Africans must dictate to their politicians, not the other way round. The 62.15% of voters who voted for the ANC aren’t idiots – they did so for any number of reasons, most of all because the ruling party represents the best worst option, if not the spiritual home many claim it to be. But what if that 62.15% began imposing? What if that cohort began asking for the best possible future, not for a barely acceptable present? Then, I think, we would have the makings of a country.”

The election results had ensured it would be business as usual for the ANC – but not for long. In the same vein as Voltaire’s famous take on God, if Malema did not exist, it would have been necessary to invent him. The relative success of the EFF in the 2014 elections, despite having been formed less than a year previously, suggested that South Africa had some degree of appetite for something different to what the ANC and the DA were offering.

South African politics was always destined to see the rise of a Malema at some stage, because as the ANC settled into power it shifted towards the political centre, leaving a gaping void on the left. Many of those who had been the ANC’s most prominent leftists – the trade unionists, communists and socialists – either became millionaires in business or stayed in government and got their piece of the pie. They still knew the songs and were fluent in the rhetoric when they had to be, particularly to keep the zombified Tripartite Alliance staggering forward, but the gap between their ideologies and their actions was growing. When communist ministers don’t blink an eye when maxing out the departmental vehicle budget on R1-million+ German sedans, you know the ANC’s left is only left with lip service.

Poplak says: “Because the South African left had effectively dissipated, I thought it was meaningful that a leftist party would rise from the ashes of the ANC Youth League, and however chimerical that may or may not have been, at least it injected a certain consciousness into the population once again. You had CEOs agreeing on record that, ‘much of what Juju says makes sense. Ja … it makes sense, buuut, we’ve just got to do it in a nice way.’ Malema’s pitch was, ‘You listen to me and do it my way, because I promise you, 60% of the country is ready to pick up pitchforks and fucking come to your house and take it.’ Take the land debate. There would be no land debate without him. We’d still be ticking along, and I feel that’s the manifest, original sin in this country. Land redistribution never happened effectively or meaningfully. So there was lots of good to Juju.”

One thing Malema has always been undeniably good at: the art of political speech-making.

Grootes says: “I remember writing a piece around 2012 where I said, ‘Julius Malema is the most gifted speaker of political English in the world.’ At the time everyone was talking about Barack Obama and how good he was and Branko, though he might deny this now, took that comment out of my piece and sent me a message saying, ‘There, I saved you.’”

But Grootes is confident that his belief still holds true. “In 2011 it was the local government elections and there were several things happening around that. Malema [still ANCYL leader at the time] went to FNB Stadium, right outside Soweto, filled with 90,000 ANC supporters. No one reported on Zuma’s speech that day. They all reported on what Malema said, which was: ‘The DA is for white people, the ANC is for you.’”

To Grootes, that line summed up the reality of politics at the time. “It was everything. I spoke to one of the DA’s chief strategists years later and he said that that was the statement of that year. No one could have done that in that way. Maimane, the mini-Obama of Soweto, isn’t as funny. It is literally, the DA is for white people, the ANC is for you. That was politics at the time. He had that ability that so few other people have had and he still has it.”

Daily Maverick and Scorpio investigative journalist Pauli van Wyk agrees. “They were the first people to call Zuma a criminal in Parliament. The DA or the Freedom Front never did that. There are quotes of Malema saying, ‘I am not going to allow a criminal to speak in this House.’ It was just amazing.”

“For the first time in years, Parliament was not just a place where the ANC MPs came to ignore the DA, grab a free lunch and catch up on some sleep.”

For the first time in years, Parliament was not just a place where the ANC MPs came to ignore the DA, grab a free lunch and catch up on some sleep. It was a battlefield, both in the verbal and physical sense. The noise coming from the EFF was something the ANC had not experienced before: a taste of their own ANCYL-flavoured medicine, repackaged and targeted directly back at them.

“When the EFF says it has made sure no one in Parliament sleeps any more, that hits the nail on the head,” says Daily Maverick’s parliamentary correspondent Marianne Merten. “Call their strategy and tactics disruptive, bloody-minded or whatever you’d like, but everyone had to up their game – the governing ANC that had long been accustomed to using their numbers to get their way without much fuss; and the broader opposition that, having seen a gap open, started working in a united front on key issues as never before.”

The EFF’s breakthrough smash hit came with “Pay Back The Money”: a chant aimed at shaming Jacob Zuma into repaying the millions wasted on his Nkandla chicken run, firepool and other “security upgrades” subsidised with state money. It was a slogan perfect in its simplicity. Even Juju’s most dyed-in-the-wool haters in white suburbia took up the refrain.

Poplak says: “What’s the demagogue’s best gift? It’s how he speaks in front of thousands and thousands of people. Malema is a brilliant wordsmith, a brilliant speaker. He can work any room. He is brilliant in front of people, one-on-one less so. He can be very warm and very ingratiating, but he’s a pure orator. Zuma never was, in Zulu or English. I remember the first time I heard Malema speak in red overalls – he was amazing. His turns of phrase. Without that, what tools does he have? Their policy has always been a bit flip-flop, their electoral manifestos are garbage, but he’s a man who comes up with #paybackthemoney. It’s just so simple, it’s brilliant.”

Merten recalls the moment when something definitively shifted in the atmosphere of Parliament: “On 21 August 2014, police stayed out of the House after the first ever ‘Pay back the money’ chant suspended then-president Jacob Zuma’s first Q&A after the 2014 elections. The SAPS members in their body armour remained just outside the doors to the chamber while the officers went inside on the floor to chat with the security ministers. Three months later that changed: on 13 November 2014, during a late-night session. During a debate on the Grand Inga hydro-power treaty, six policemen in body armour moved in to remove the EFF MPs after their MP Reneiloe Mashabela had called Zuma ‘thief’ and ‘criminal’.”

For Merten, it was a defining moment. It had never happened in the 20-year existence of the democratic Parliament. It simply wasn’t done. She says: “That invasion of police onto the floor of the House broke something for me. It was the manifestation of how the legislative arm of the state had subjugated itself to the executive and allowed the police, part of the executive sphere of the state, unfettered access.”

Unperturbed by their regular ejections from Parliament, the EFF would later hit on another spoken-word winner, “uBaba ka Duduzane” (the father of Duduzane) which they used to refer to Jacob Zuma at a time when his son Duduzane’s name was constantly in the news in association with the Guptas. Also in the South African lexicon thanks to EFF: the term “Zupta”, a wonderfully contagious portmanteau of Zuma and Gupta, which like an exploding ATM stash of indelible ink permanently stained government ministers and toadie officials implicated in the treasonous fire-sale of South African parastatals.

Now-former ministers Malusi Gigaba, Lynne Brown, Nomvula Mokonyane, Faith Muthambi, Mosebenzi Zwane, Brian van Rooyen, Bathabile Dlamini and David Mahlobo as well as parastatal CEOs like Brian Molefe and Matshela Koko, and the Hawks and SARS bosses, Berning Ntlemeza and Tom Moyane – they all got the Zupta baptism, the Saxonwold shower.

SARS wars

From early on in the Zuma years, as the kleptocracy kicked into gear and brazen theft from the public purse was made apparent almost daily by Daily Maverick and other news outlets, it was hard to know where to look for reassurance that justice would be served and that the bad guys would get their comeuppance. The ANC showed no signs of casting off its bad apples, while the police and the NPA revealed themselves to be either toothless or complicit.

There was, however, one state institution that remained not just intact, but highly effective. That body was the usually profoundly unsexy tax-collector, SARS.

Forget SWAT teams and CSI labs: if South Africans who dabbled in white-collar crime feared anything, it was SARS, because the revenue service was more effective than any law-enforcement agency in bringing crooks to book. But as Zuma began his second term as president in 2014, what remained of SARS’s independence and efficiency was about to be obliterated.

Pauli says: “SARS were extremely effective in investigating tax schemes. They had a well-developed investigative department. But SARS also wasn’t as hellish in practice as a SARS investigation can be under our tax laws, because it was trying to look after the people of the country as well. You have to remember, SARS worked against the backdrop of apartheid where people withheld tax as a sort of a push-back against the system. Many did not want to support a state that wanted to kill or suppress them in return. South Africa did not have a tax-paying culture, so after 1994 SARS had to develop that by not using the carrot instead of the stick from the beginning. They had to tell people that this is the right thing to do and this is how you do it. They would use encouragement and development and educational programmes to ensure that the broader population understood why it was important to pay your tax. They would only use the enforcement department, the investigative arm, when it was absolutely necessary and when it was required for serial offenders.”

So SARS were good guys, accountants high on ubuntu, the perfect balance of understanding and authoritarianism. Still, for revenue services to work, the premise that the rules apply to everyone must actually be applied. Those who can pay taxes, must do so. However, if a sitting president also happens to double as the nation’s very own carrot and stick‑resistant Al Capone, then South Africa as a nation and SARS as an organisation have one helluva problem.

“But why would any sitting president want to weaken the revenue service, the organ of state responsible for bringing in the taxes that stoke the economy?”

But why would any sitting president want to weaken the revenue service, the organ of state responsible for bringing in the taxes that stoke the economy? It’s like riding a bicycle and deciding to poke a stick between the spokes, then blaming the bike for your crash. Pauli has some potential answers.

“Zuma had, or has, two fears in life, and every decision that he made was based on those fears. The one was going back to jail. You can see that in all the decisions he made about the justice cluster. Even before he was elected as president, he initiated a movement to get hold of state security and crime intelligence. Then, when he was in power, the very first move he made was to appoint a new head for the NPA, Menzi Simelane, which was a disaster. It was the first decision of Zuma’s that the courts reviewed and set aside. All his subsequent decisions – injecting Nomgcobo Jiba into the NPA, pardoning her husband, the appointments that he has made – all of them were designed to ensure the prosecuting authority does not come after him.”

She continues: “The second fear that he has is to be poor again. For Zuma, money is like opening a tap. You would think that he stole a lot and squirrelled it away somewhere. That’s not how it happened. For Zuma, just the knowledge that there’s a tap that he can open and close – that was his thing. He wants to secure a lot of people that can give him money on request.”

In summary: “People don’t understand Zuma, and they can’t understand why his decisions don’t make sense to them. But if you understand those two fears and measure that against his decisions, everything makes sense. Everything clicks. That’s what happened over the past decade. Every little thing that we went through will be against the backdrop of, and was influenced by, those two fears. It seems like chaos, but it’s not. It’s very organised, very basic and very crude. I don’t want to go to jail and I don’t want to be poor.”

The problem for Jacob Zuma was that those two drives were fundamentally at odds with each other. In his quest not to be poor, he engaged in behaviour that should, technically, lead him back to jail. While he had successfully captured or de-fanged the criminal justice sector, SARS was another story. It was virtually inevitable that the high-functioning tax body would eventually beat its way to his door.

Pauli says: “When Oupa Magashula and Ivan Pillay were in charge of SARS, Zuma already had all these tax issues, plus he had a son, Edward, who worked with some of the tobacco barons in KwaZulu-Natal.”

There’s a VIP unit inside SARS that assists judges, ministers, presidents, deputies, with their taxes. The concept behind the establishment of this unit was to help the executive be above suspicion.

Says Pauli: “Every new president gets help from SARS to regularise their affairs. The same thing happened when Zuma ascended to the presidency, and he did not like it at all. Zuma had tax problems and they tried to help him. He had all these foundations and his wives had all these foundations, and they were all checked and none of them were tax-compliant. They also investigated ATM (Amalgamated Tobacco Management) in KwaZulu-Natal and SARS stumbled upon Edward, and it was clear that there was a big tax problem there as well. So Zuma sort of had the idea that SARS was investigating him. In the process of SARS trying to regularise his tax affairs, he was scared that they would stumble upon everything he has done, all his sources of funds, because Zuma has a myriad sources. And SARS were busy investigating them. He did not want to allow them anywhere near his affairs.”

Malema, unable to shake some of the teachings of his former leader, experienced the same issues. Pauli says: “Malema was warned many, many times and he just refused to listen, and in the end SARS realised that they would have to enforce decisions on him. That’s why he ran into tax problems, because he would not listen, not because SARS decided to slap him with a huge tax bill. SARS was well-developed and well-accustomed to a very specific South African problem.”

When he was deputy SARS commissioner, Ivan Pillay visited President Jacob Zuma several times between 2012 and 2014 in an attempt to get him to sort out his taxes. Zuma, who allegedly did not file tax returns during the course of his first term in office, stalled and stalled again (hello, Stalingrad strategy). He had zero interest in allowing Pillay and his investigators to look further into his finances. Frustrated, Pillay offered to resign. In classic Zuma style, the president told him that was not necessary, and then a few months later appointed Tom Moyane to head up SARS. A former prisons commissioner, Moyane had also been on the four-person panel that whitewashed the investigation into the Waterkloof Gupta plane landing. For SARS watchers like Pauli, it was clear this was never going to end well for the revenue service.

Competition for the title of ‘most destructive appointment’ made by Zuma during his presidency is fierce.

Competition for the title of “most destructive appointment” made by Zuma during his presidency is fierce. Tom Moyane might not seem like a frontrunner: the SARS commissioner initially kept a fairly low public profile. Ultimately, however, what Moyane did to SARS – with the helpful aid of multinational management consultancy Bain & Company – caused South Africa catastrophic damage.

But Pauli was on his case: tracking Moyane’s every move right up until President Ramaphosa relieved him of his position after the findings of the 2018 Nugent Commission of Inquiry into governance and administration issues at SARS.

“I wrote about how Moyane came in, how his appointment was decided a year before, how Bain & Company tried to get work in South Africa, how they wooed the president, how a fixer of Zuma’s, Duma Ndlovu, was paid kickbacks to ensure that Tom Moyane could get into SARS,” says Pauli. “Bain & Company and Tom Moyane knew about this appointment, that it would come up, almost a year before it would happen, which is terrible. When Moyane came in, Bain & Company wanted to make a lot of money. They needed to overhaul the system. That suited Moyane because it would break down the system and give him the chance to get rid of a lot of people.”

When Moyane was appointed SARS commissioner in September 2014, he was taking the reins of a body considered an international model of best practice.

Pauli says: “In 2013/start of 2014, SARS was the crown jewel of our state departments. It was extremely effective. It won international accolades. The Americans asked to work with SARS, which is something that just doesn’t happen. If the American justice system asks to work with a developing country’s state entity, that’s a huge thing. They sent out a formal letter – ‘can we have this relationship, working together’. SARS said yes. Then Tom Moyane came in, and while the Americans never officially retracted that relationship, they never shared anything since then, so that dried up.”

Moyane came in with a specific mission: to gut SARS from within. He was also fighting fit, as he had been coached by Bain & Company since at least October 2013 on who to target at the revenue collector when he eventually got the job. Moyane started by persecuting top management and investigators. Many were swiftly driven out; among them, SARS chief information officer Barry Hore.

In a December 2014 email exchange reported on by Pauli between Bain partner Fabrice Franzen and Bain’s South Africa head Vittorio Massone, it was clear that they were shaken by the clinical efficiency with which Moyane was dispatching senior management. This was despite the fact that resignations like Hore’s stood to benefit Bain by profiting from the purge of skilled personnel at SARS.

Franzen had written: “Goodbye Barry Hore…”

Massone responded: “Now I’m scared by Tom… This guy [Hore] was supposed to be untouchable and it took Tom just a few weeks to make him resign… Scary…”

With Bain advising him, Moyane both robbed SARS of its best people and disbanded its highly effective investigative units in an overhaul that had a monetary cost to the taxpayer of R187-million (Bain’s fee), but which cost SARS and South Africa a lot more in terms of the sustained damage inflicted on the revenue service.

“Moyane was not only going after people within SARS. He was also looking to take down ex-SARS staffers associated with one man in particular: then-Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan…”

Moyane was not only going after people within SARS. He was also looking to take down ex-SARS staffers associated with one man in particular: then-Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, who had been SARS’s first commissioner from 1999 to 2009. Gordhan was proving to be a massive thorn in the side of Zuma, repeatedly impeding attempts to get National Treasury to open the tap. Gordhan needed to be publicly discredited so that it would be easier to get rid of him.

Enter the “Rogue Unit” narrative. This was the story first willed into being via a botched KPMG investigation, which claimed that Ivan Pillay and fellow high-ranking SARS officials Johann van Loggerenberg and Andries Janse van Rensburg had covertly intercepted NPA communications, carried out illegal surveillance, and even run their own brothel.

The Sunday Times picked up the story and ran with it on cover after cover throughout 2014. Branko says: “The Sunday Times was really pushing the Rogue Unit story. It was completely 180-degrees fake news. So people were talking about what the Sunday Times was doing more and more instead of what was really going on. We could not believe it. Surely they are not talking about this? Everyone involved in the Rogue Unit story was a friend of Pravin Gordhan – Oupa Magashula, Ivan Pillay, Johann van Loggerenberg – so by association Gordhan was ‘tainted’. We knew all of this, but they fell for it.”

Whether Sunday Times journalists helped disseminate the Rogue Unit narrative knowing it was false, or whether they were unwittingly used as pawns, is still unclear. It didn’t matter. By the time the KPMG report’s failings were exposed, and the Sunday Times had retracted its reporting on the matter, the damage had been done.

The Rogue Unit story provided fodder for a political witch-hunt that the forces of State Capture continue to attempt to revive to this day. Former top prosecutor Shaun Abrahams, another key Zuma appointee, would try (and fail) to press criminal charges against Gordhan for another SARS-related fiction linked to the early retirement of Ivan Pillay. In 2019, Public Protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane would once again pick up the threadbare tale of the Rogue Unit.

A somewhat Payneful experience

Not many people are familiar with the work that goes into Daily Maverick’s somewhat famous newsletters. Before newsletters became the lifeblood of many newsrooms around the world, Branko and Phillip had recognised the importance of a quality newsletter to accompany the editorial work produced for the website: not merely an algorithmically produced export of the latest stories, but a hand-crafted, human-infused effort that would deliver the most important overnight happenings and upcoming events for the day, wrapped up in dry wit, delivered to inboxes by 6am each weekday morning.

“You can imagine there aren’t too many people skilled or mad enough to undertake this effort as part of their normal workday.”

You can imagine there aren’t too many people skilled or mad enough to undertake this effort as part of their normal workday. But the toil has paid off: one slightly perverse indication of the popularity of the newsletters is that some members of the public apparently retain the belief that Daily Maverick is only a newsletter service. Imagine their delight when they find out about the website!

Styli says: “Just as we changed newsletter editors over the years, so too we searched for the best newsletter platform. In the beginning and in an effort to keep things local, we worked with an outfit called Everlytic, and our login to the newsletter content management system was the url emma.dailymaverick.co.za. We have no idea who Emma is or why that was assigned to us. We subsequently moved onto Mailchimp and then another local outfit called TouchbasePro. But each day, while still on Everlytic, whoever our editor was at the time would don their WWF outfit and get ready to wrestle with the dogmatic system before the sun was up.”

Following Phillip’s stint as First Thing editor were Simon Williamson and Simon Allison – who, says Styli, “had the benefit of the Hong Kong time zone, and sipping Mai Tais, to compile the newsletter” – with brief stints from Sisonke Msimang and Carla Lever. Then John Stupart was handed the keys to what Styli calls “one of the most important vehicles in our fleet”.

Just before Stupart became newsletter editor, Daily Maverick had a period in 2014 where the bleary-eyed task to get First Thing out the door each morning was split between a few of the team members who had endured stints in the hot seat before. Khadija, Greg and even Styli all took the reins while they waited for Stupart’s notice period to run out the clock.

Styli says: “Because we didn’t want to chop and change the newsletter editor byline each week, we created a pseudonym in tribute to the original system: ‘Emma Payne’. The internal joke had us laughing for weeks and was in some sense cathartic payback for all the pain Emma had caused us.”

Styli recalls his stint during the 2014 Soccer World Cup in Brazil. “Matches would run until about half-past midnight, which meant staying up until then for the final score and producing a summarised match report to include in the newsletter, along with all the other info that could be prepared for the 6am send. This would be followed by a 5.15am rise to check for the biggest stories that had broken in the interim, and including one or two big pieces, before sending to the sub-editor for checking.”

Unsurprisingly, he says, all the dry-wit titbits were included in the first shift before midnight. Emma Payne tended not to be in sharpest form at dawn.

Says Styli: “As the Daily Maverick team grows, it’s funny how some new employees still remember Emma Payne – and how distraught they are to find out she was this Frankenstein effort of available and quasi-willing staff to keep this important cog turning.”

Bad for the nation, good for the business

Any journalist who enters the profession in the hope of getting rich is either deluded or open to corruption. For South African journalists, it’s a matter less of a job and more of a compulsion: a driving desire to make a contribution, expose the corrupt, hold power to account. So, when the country is circling the plughole, journalists find themselves in a conflicted space – plenty of juicy material to write about, but also plenty to despair over as ordinary citizens.

“In the media world, when South Africa is in the doldrums, it’s actually good for business.”

In the media world, when South Africa is in the doldrums, it’s actually good for business. 2014, with the Pistorius trial, the Nkandla debacle, the phoenix-like rise of the EFF, the general elections, and the dismantling of SARS, saw Daily Maverick’s readership grow to a record 15,000 a day. More readers meant more investment, and for Styli, fundraising was always either happening or preparing to happen.

The growth in readership coincided with a time that the US media scene was attracting a lot of venture capital and private equity funding. Styli used those (now crazy) valuations to show that Daily Maverick wasn’t completely insane when putting together investment proposals. Daily Maverick was making waves – and it was this societal impact that clinched the investment in equity-raising. Despite the much-needed cash injection, it was still not enough money for the extravagant luxuries of an actual office. But it felt like progress, in the most bittersweet way.