There will be blood

It would become a defining year, for the country and for the publication. But first, there was a massive hole in the Daily Maverick team to fill.

Grootes’ departure had left Branko without a senior political reporter. He knew who he wanted: former political journalist of the Sunday Times Ranjeni Munusamy had been working as a freelance sub-editor for Daily Maverick. Ranjeni was the obvious choice to take the reins, but it took some doing on Branko’s part to persuade her.

“She had suffered a lot after the Bulelani Ngcuka spy story scandal while at the Sunday Times,” Branko says, in reference to the ultimately false allegations, which surfaced in 2003, that former NPA head Ngcuka had been an apartheid informant. The fallout from the story, Ranjeni would later write in a candid Daily Maverick column, had “banished [her] to the fringes of society” and saw her take up work in support of then-deputy president Jacob Zuma: a politician with whom she had since grown deeply disenchanted.

Says Branko: “I had to really convince her to go back into journalism and into the limelight.” As many have observed, Branko is a difficult man to say no to. Ranjeni agreed to join the Daily Maverick’s writing team – and not a moment too soon. 2012 was to be an extraordinary year for journalism, and Ranjeni would soon prove herself once again as the heavyweight journalist that Daily Maverick needed.

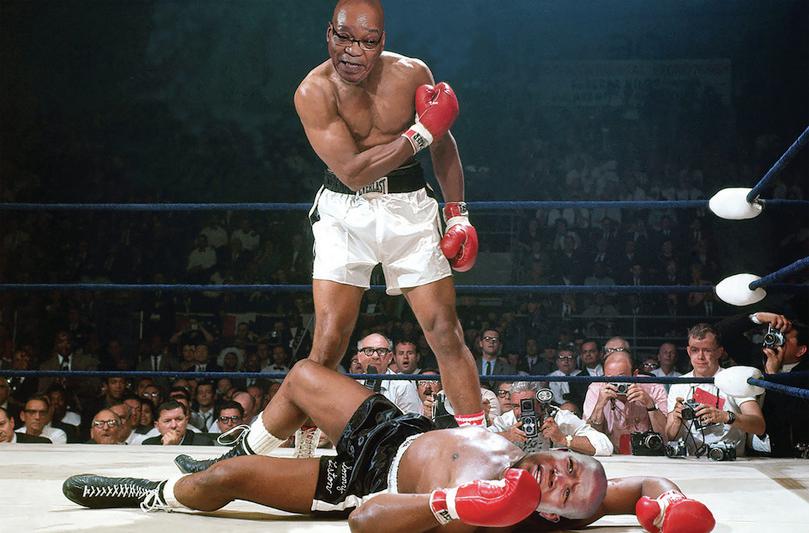

Juju – out for the count

It was predictable that the perennially pugilistic Julius Malema was not going to take his suspension from the ANC lying down. With his sanction still to be formally pronounced, Malema publicly called President Zuma “a dictator” and thus sealed his fate beyond any doubt.

In April, Daily Maverick led the news of Juju’s summary expulsion from the ANC with an image of the prostrate former Youth League president, lying on the boxing-ring floor after Zuma’s knock-out punch. This visual comment was produced by Daily Maverick’s in-house Photoshop specialist… Branko. “Malema is once, twice, three times suspended,” declared the headline in the unmistakable rhythm of Lionel Richie’s famous song.

With Malema out of the ANC within the first quarter, 2012 was to be one year of the last decade in which the former ANCYL leader would not hog the majority of the annual headlines. There was more than enough to keep journalists busy in his temporary absence. Come May, the South African news cycle would find itself – for possibly the first and only time in history – dominated by the story of a single artwork.

The art of war

Of course, the drama surrounding Cape Town artist Brett Murray’s The Spear painting was barely about art at all. It spiralled with bewildering speed into a landmark debate about freedom of expression. The painting in question depicted President Jacob Zuma in a Soviet-style stance, his genitals on brazen display. It was an audacious comment on a president whose sex scandals for years made for febrile national discussion, from his rape trial to his many wives. It was also a comment which many considered both racist and insulting.

It was when the artwork was defaced while on display at Rosebank’s Goodman Gallery that the story ignited from glowing coals to the status of full-blown conflagration. The moment Louis Makobela and fellow Spear vandaliser Barend la Grange drenched the painting in black and red paint, it became a living installation, the memory of what had been covered now even more deeply etched into the public psyche. Zuma’s genitals became tragically hard to unsee.

The resulting debate ran in media outlets across the world, including Fox News, AFP, the global Huffington Post site, ABC Melbourne, the Scotsman, the New Zealand Herald and the Global and Mail Canada. Spear divided even Daily Maverick writers.

Greg Nicolson gave readers the dramatic scenes of protest outside the gallery. Sipho described it as a “picture that conjures up years of black humiliation at the hands of white apartheid power”, and mused: “I wonder if Murray might have come up with a different visual metaphor had he considered that the effects of apartheid might cause millions to be insulted.”

Chris Gibbons summarised the fracas: “What it really showed was exactly how divided we still are, which means we still don’t have a clue who we are.”

When the gallery eventually took down the painting, they sent it to its German buyer – who was reportedly unperturbed by its defaced form. After all, few things are better for art’s value than controversy. But when shock-jock artist Ayanda Mabulu attempted to repeat the stunt later the same year with a similar painting titled Umshini Wam, nobody seemed able to work up a commensurate amount of outrage. “We’re all still recovering from a severe bout of Spear fatigue,” suggested Rebecca Davis by way of explanation.

“Outrage” is an overused word in a time of knee-jerk social media overreaction. But the horrified national response to events that would take place in South Africa’s mining belt in late August of that year would restore the word to its appropriate meaning.

The cold murder fields of Marikana

Marinovich says that, for him, this picture defines the tragedy’s watershed symbolism.

“It’s one that wasn’t used – the one of the suicide at Small Koppie, months after the massacre. The miner’s body had been taken by the time I saw it, thankfully, but the strapping he had hanged himself with was still on the tree. It was the same that is used to close the platinum ore bags. It was a very banal image,” says Marinovich.

The suicide victim was Lungani Mabutyana, aged 27, but Marinovich had been forced to set aside the story. The unfolding chaos after the massacre had subsumed him into other investigations in Marikana, including those looking into assassinations and attempted assassinations.

“He was one of the survivors of the shooting – probably Scene Two – which is where he killed himself eventually. He had been arrested on 16 August, along with some 200 other survivors, and most likely charged with murder. All survivors were, as far as I know. The tree he hanged himself from was alongside the tree where Mr Nkosiyabo Xalabile’s body was found [body O, according to forensic evidence]. On the day I went to the scene of the hanging with miners, we found several presumably police-spent cartridges from the 16th just 2,8 metres away,” says Marinovich.

Daily Maverick’s reportage on the massacre of 17 Lonmin miners around a kraal at Thaba koppie, as well as Marinovich’s exposé of the cold-blooded murders of 17 more striking miners at nearby Small Koppie just minutes later, would show that police brutality that day went far beyond injustice. It dehumanised the lives of human beings to the point of banality.

“He hanged himself in despair after losing his job and burdened with debt… At least seven miners were known to have committed suicide by this date,” wrote Marinovich in his notes.

The suicides after the Marikana massacre were a barely publicised footnote to the main acts of violence. Sidelined by British company Lonmin’s wobbly transformation attempts under the guidance of then-non-executive director Cyril Ramaphosa, the striking miners of Marikana – led by the rock drillers – had been prepared to die for a living wage increase from around R4,500 per month to R12,500 per month.

In the days leading up to the massacre, the 112 Lonmin miners who would end up either wounded or killed in a storm of police bullets had become embroiled – along with several thousand other strikers – in hyper-violent and deeply politicised wildcat skirmishes between members of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), the ANC-aligned National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), Lonmin security services and the South African Police Service (SAPS).

But not even the miners’ pre-massacre battles against unconscionable working and living conditions could validate the ferocious incidents in which two policemen, two Lonmin security officers and six miners lost their lives in the days around the weekend that started on Friday 10 August 2012. Ten people were bludgeoned into sacrificial lambs by the cause – and the murders certainly fomented tensions between the aggrieved strikers and the police.

Marinovich would write for Daily Maverick that “gruesome cellphone pictures” of the two policemen hacked to death in an act of brutal thuggery “were circulated throughout police circles”. There can be no doubt that the murders of the policemen far exceeded the boundaries of self-defence and, the veteran photojournalist added, the police would be sure to “view the killing of their own with extreme anger”.

Given his track record as a Pulitzer-winning conflict photographer, Marinovich could have represented any number of international news organisations while reporting in the dust-addled North West mining belt. However, it was Branko’s spirit he decided he “liked” after first meeting the editor at the ANC’s national conference in Polokwane, back in 2007.

Marinovich’s work on the Marikana massacre would deliver some of his career’s most impactful investigations – and establish Daily Maverick as a vital truth-telling voice amid a murky sea of lies, cover-ups and obfuscation.

“Marikana was hell”

On the afternoon of 16 August, Branko’s phone pinged with a message from Ranjeni. “Are you seeing this?!!!!” it read. What would become known as the Marikana massacre was literally unfolding in front of rolling TV cameras.

“I had been badly sick in bed – I couldn’t move,” Branko recalls. He asked the Daily Maverick political reporter to be his “eyes”.

Marinovich would be on the scene by 5am the next morning, collecting observations of just how little human life seemed to mean after the massacre.

“As police forensics experts gather evidence under spotlights, they run out of formal cones to mark the points at which evidence is gathered. They turn to using their polystyrene coffee cups as markers,” Marinovich reported for Daily Maverick.

“On the other side of Wonderkop shantytown, striking miners gather on a dry, overgrazed field outside to discuss their response to the massacre yesterday that saw more than 30 people killed by police gunfire. A miner who refuses to be named says, ‘The police are meant to protect us, but they only kill us.’ Others around him murmur their assent, adding, ‘They did not even warn us, they just started shooting.’”

Once recovered from his illness, Branko would halt his daily operations in Johannesburg and travel to Marikana to see for himself the effects of that bleak, blood-soaked afternoon that he – like most South Africans – could barely bring himself to believe had really happened.

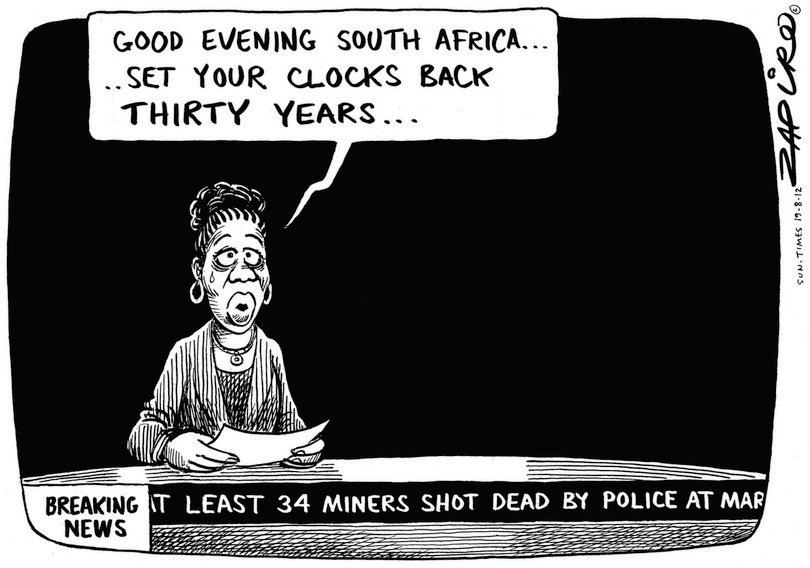

“It felt like we’d slipped back into apartheid, less than two hours from Johannesburg’s shopping malls. Two hours – but 200 light years.”

“Marikana was hell. I was there three or four times in that month. I thought I had a pretty good idea of what was going on in South Africa. Then you get to Marikana. You get behind the numbers and the data, and you see the real suffering. It felt like we’d slipped back into apartheid, less than two hours from Johannesburg’s shopping malls. Two hours – but 200 light years.”

He was one of the few editors in charge of a news organisation to leave his desk to visit Marikana, joining Marinovich – known among staff by his wife Leonie’s nickname, “Bokkie” – on the front lines.

“Bokkie was incredible,” Branko recalls. “He went there every day, took pictures, formed friendships with people, shadowing the protesters. He went down into the mine. He became a kind of local hero, and it was because the locals could see he was about much more than just genuine interest. While everyone else seemed to forget about Marikana after a few days, Marinovich was there for the community, keeping the story alive. People weren’t his commodities.”

Fellow Daily Maverick reporters Ranjeni Munusamy, Khadija Patel, Sipho Hlongwane and Mandy de Waal would fill out the rest of the editorial corps reporting on the immediate developing story. (The original reports from Marikana’s initial killings were filed by Greg Nicolson, who subsequently left for Australia on a long-before planned family trip.)

Khadija, today editor-in-chief of the Mail & Guardian, recalls the repercussive shock she felt watching the televised massacre. If anything, she knew her leave was over.

She recalls arriving with Sipho in Marikana’s simmering, brawny dystopia, feeling not only the weight of Sipho’s nerves over how local machismo might receive her Muslim headscarf, but of her own.

“Marikana was weirder than anything I had imagined. There was this big-ass mine towering above the earth, looming over the shantytown and, next to it, a KFC, of all things.”

And yet Khadija describes reporting on the events at Marikana as her “favourite time” at Daily Maverick: “We were bonded as a team; we were working around a story that we understood was important and that we were doing better than anyone else,” she says. “There was also this bravado that defined Daily Maverick. We thought of ourselves as better than anyone else. That was the DNA of DM. Marikana was an opportunity for us to show that.”

Whispers of a second “kill site”, as it came to be known, had been circulating widely.

“As Jacob Zuma attempts to contain the damage of the Marikana massacre by promising a speedy enquiry, researchers, activists and rights officials at the scene of Lonmin’s killing fields are accusing the police of tampering with evidence,” Mandy de Waal reported. “Even worse, a theory is emerging that the police manoeuvre at Marikana that left so many miners dead was a deliberate and deadly act.”

University of Johannesburg Professor Peter Alexander, who had been on site, told Mandy that police at the killing scene had destroyed evidence. “Clearly the police have been removing evidence without there being any independent investigator present,” he said. “But there is some evidence that they cannot remove, and that is the scorched grass. I think it would also be quite difficult to remove the pools of blood, which show that there was more than one killing site at Marikana.”

Perhaps the police had counted on the fact that Marikana’s history would be a version of events told through tame reporters’ eyes, neatly overlooking the partnership Bokkie had struck with Alexander’s pioneering University of Johannesburg team.

Apartheid déjà vu

By the time Marinovich reached the foreboding crime scene of Small Koppie, the words of a miner he had interviewed after the massacre had been echoing through his mind: “Nobody expected to lose their lives here; this is too much. If management would agree to increase our wages, we would go back to work tomorrow.”

Marinovich was surrounded by the forensic paint markings denoting the miners who had been gunned down at close range, away from the news cameras.

The message from the dead was grim: he’d have to be the first journalist to tell the world that, after all these years, South Africa remained the surreal incarnation of an apartheid-style police state.

“I physically felt my chest grow constrained – I guess it was blood pressure – as it looked like one of the many places I had seen where there had been killings. There was déjà vu. I also felt a combination of horror, anger, disappointment and journalistic promise,” Marinovich recalls.

Marinovich knew something had happened at the small koppie, but the story took weeks to write. He went back and forth with Branko. He tried to get eyewitness accounts, only to realise that any of the striking mineworkers who saw what happened were either dead, injured or arrested. Later he would write about how those who were arrested were tortured while in custody. The dominant narrative was that the mineworkers were muti-crazed, hell-bent on violence. The police needed to defend themselves.

But when Marinovich finally published his definitive story on 30 August 2012, the police were exposed. His article – “The murder fields of Marikana. The cold murder fields of Marikana” – would also decisively expose the bloodbath of 16 August 2012 as the day that rewrote post-apartheid history. The headline was brainstormed by Branko in the early hours of the morning.

“When Greg told me about the second scene, about the horror he had uncovered at Small Koppie, I was almost not computing. What’s funny is that I have a really good memory, but I’ve almost no memory of that night when I published that piece,” he says. But he does remember, in finalising the piece for publication, “trying to be poetic and driving the message of horror. Murder. COLD murder.”

The opening lines of the story were even more damning. “Some of the miners killed in the 16 August massacre at Marikana appear to have been shot at close range or crushed by police vehicles. They were not caught in a fusillade of gunfire from police defending themselves, as the official account would have it. GREG MARINOVICH spent two weeks trying to understand what really happened. What he found was profoundly disturbing.”

Marinovich had pieced together his account through interviews with surviving strikers and researchers and through a painstaking examination of the massacre site.

What he found showed convincingly that the casualties of police violence on the day of the massacre numbered 112: a figure Branko drummed into the heads of the Daily Maverick staff assigned to report on Marikana.

“Let there be no doubt: on 16 August 2012 the SAPS shot 112 people. That’s the murder of 34 human beings and the attempted murder of a further 78.”

Denial, backlash – and plagiarism

Branko had gone to sleep in the early hours of 30 August knowing that the publication of Marinovich’s Marikana expose on Daily Maverick would have a seismic impact. But even he was unprepared for the “absolute chaos in the country” that he encountered upon waking.

“At first there was a massive wave of disbelief,” he says. “The sense was that the police would never do this to their people in democratic South Africa.”

The South African Press Association, Sapa, published an interview with Dr Johan Burger, a senior researcher with the Institute for Security Studies – “a former police guy who rubbished Greg’s story”, says Branko. “One guy. Sitting behind his desk. In those days everyone, except us, was publishing Sapa stories on their website by default. The result was a flood of national coverage critical of Greg’s investigations, which showed convincingly that police had killed people on purpose.”

News24 ran the Sapa piece, headlined “Journo’s account of shooting questioned”. It quoted Burger as terming Marinovich’s story “wild in terms of its accusations and assumptions”.

There was nothing for it. Branko got on the phone and started calling editors in rival newsrooms.

“I personally begged the doubters to go and see the Small Koppie murder scene for themselves. They wouldn’t go,” says Branko. “They were parroting the Sapa official line, staying behind the police lines. But I guess that’s what happens when you commoditise news. Marikana was a failure of journalism, which I believe was down to sincere incompetence.”

Nonetheless, the implications of the investigation could not be ignored. Marinovich’s piece was republished in several South African newspapers, with permission from Daily Maverick. Momentum shifted from denial to national anger when, on Sunday 2 September, Carte Blanche aired Marinovich’s investigative footage.

Less welcome TV coverage came in the form of a Sky News piece in which the broadcaster’s Alex Crawford claimed to have uncovered the truth about the Marikana massacre – presenting Marinovich’s findings as her own.

The Daily Maverick team were enraged. Styli emailed Crawford requesting a meeting, while Branko shot off a mail to the Guardian in London laying out the context for their unhappiness with Crawford’s conduct.

“We are disturbed and disappointed by Sky News’ recent feature, broadcast on 6 Sep 2012, regarding the shooting of striking miners in South Africa,” Branko wrote. “The broadcast follows the exact same steps as our journalist did over a week ago, when we broke the story to the world. Sky did not acknowledge any of the work done by us breaking this story, and through their silence represented the work to be their own. We feel this is outright and blatant plagiarism.”

Crawford’s emailed response was one of polite bemusement, expressing her belief that Daily Maverick’s “concerns about the story are unfounded”. She claimed that her team had spoken to “entirely different witnesses and survivors” to Marinovich, who “all reported back the same story”. Crawford said that her story had also leant heavily on the research undertaken by Professor Peter Alexander – as had Marinovich’s.

“We felt we went out and did our own journalism around it and felt it was an important story which needed to be delivered to a different – international TV – audience,” Crawford wrote.

Daily Maverick let it go: such incidents are an unpleasant but not uncommon feature of the often cutthroat world of news media. But the opportunity for a last word on the matter presented itself a few months later.

In February 2013, Daily Maverick’s Rebecca Davis produced an analysis challenging another Sky News report by Crawford on South Africa. Crawford’s story claimed that Eastern Cape women were deliberately drinking alcohol during pregnancy in order to subsequently claim a disability grant for the child. The story went on to be picked up by a number of other high-profile international news outlets.

After thoroughly assessing Crawford’s claim, Davis concluded: “The experts are clear: there is absolutely no research – and very little evidence – to support this alarming, and potentially destructive, claim.”

This reportage gave Branko an opening to insert a short but instructive footnote:

DISCLOSURE: On Thursday 6 September 2012, SKY News triumphantly ran the story by Alex Crawford, in which she, in effect, reverse-engineered Greg Marinovich’s work on the Marikana murders and presented it as her own discovery, without crediting Marinovich or Daily Maverick. Two days later, we sent a polite letter to Ms Crawford pointing out that she had not given credit where it was due. We offered to meet and resolve the issue. Ms Crawford’s response was a relatively polite but still arrogant counterattack in which she expressed confusion at our unhappiness. Those were busy days – we decided it was more important for us to continue working around the clock to uncover the full truth of SA’s most horrific post-apartheid massacre than to actually shed our politeness and unpack her transgressions point per point. In any case, we at Daily Maverick learnt about Ms Crawford’s ethics the hard way.

So yes, before you start reading this article, be aware of the fact that we’re not the world’s biggest fans of Alex Crawford’s work. When in early January Sky ran her sensational report on SA mothers’ alleged systematic drinking to cause harm to their unborn children, we were not surprised. It was the point at which we simply had to draw the line. What follows is the result of Rebecca Davis’ quest for the truth vs. Alex Crawford’s report. – Ed.

Assessing the impact

On being asked whether the “Cold murder fields” exposé was the moment that cemented Daily Maverick as a serious industry player, Marinovich says: “I think so. Probably in the fact that people in the street, or in a nightclub way past my bedtime, would approach me and say ‘keep going’ or ‘thanks’. It was at the Marikana taxi rank that a small group of people started applauding me – I was so uncomfortable but also so moved.”

When Branko calculates the impact of the Marikana story, he does so soberingly.

“If we hadn’t published Bokkie’s story, the police would have likely got away with it,” he suggests. “You could say this was not only a story about the failure of the SAPS. It was a failure of the media. That’s when I realised, ‘It’s us – it’s up to us.’ With a few exceptions, we seemed to be the ones who could defend truth. Not because the will wasn’t there. There are plenty of willing journalists, but not enough good ones. To me, Marikana was the first massive test of South African journalism in post-apartheid times, and that test was failed. Terribly. It was failed so terribly.”

Branko identifies Daily Maverick’s Marikana coverage as the first time that the publication had transformed the national conversation, rather than merely reported on it.

“The whole Marikana story was so symbolic of our fight to be heard since our inception in 2009. Ironically, I’d say it was also when everyone finally realised – our colleagues in the industry, the public and the government – that they had no choice but to take us a bit more seriously. You could say we came of age. It was here that we found our purpose to help the people of South Africa.”

“The whole Marikana story was so symbolic of our fight to be heard since our inception in 2009. Ironically, I’d say it was also when everyone finally realised – our colleagues in the industry, the public and the government – that they had no choice but to take us a bit more seriously. You could say we came of age. It was here that we found our purpose to help the people of South Africa.”

But the work came at a cost. In the past decade, there has hardly been a Daily Maverick staff writer who has not been affected by Marikana to some degree. The regular Daily Maverick feature “Reporter’s Notebook” profiled Sipho’s excoriating guilt about the massacre, and particularly the assassination of Daluvuyo Bongo, the NUM secretary at Lonmin and one of Sipho’s sources.

In “The lessons that no journalism school can teach you”, published in October 2012, Sipho revealed that Bongo’s death “changed the way I operate. It has changed how I perceive things, and it left some acutely painful questions I might never be able to answer”. He wrote powerfully of his sense of helplessness in the face of acute need: “Desperate people put immense trust in my abilities to help them when I truly don’t know what to do”.

Khadija remembers the time as one of extreme emotional stress as well. “We had many discussions in our old Daily Maverick office in Rosebank,” she says. “Our editorial meetings went on for hours at a time. We were speaking about our experiences, which was very therapeutic. It was a big lesson in understanding our own frailties. Marikana was really hard work as well as being really emotionally draining.”

One person doing a good impression of being unfazed by Marikana was President Zuma, who called the massacre a “mishap” when addressing a foreign press corps in October 2012. He went on to say that it would be inaccurate to term it a “crisis”.

Then again, Zuma had more personal fish to fry. News of the taxpayer-funded upgrades to his home at Nkandla, originally broken by Mail & Guardian in 2009, had been put back on the radar by a City Press investigation. Over time, Nkandla would grow into one of the defining thorns in the side of the Zuma presidency, and Daily Maverick would pursue the story with appropriate zeal.

But as the end of 2012 hove into view, the ANC’s 53rd national conference in Mangaung was fast approaching. The Daily Maverick’s small team had one foot still in Marikana, one in Mangaung, and whatever dangled in the middle was all that they could proffer to Zuma.

The Gathering, Vol II

The second incarnation of The Gathering, held in late November at the Victory Theatre in Johannesburg, saw several distinct upgrades on the inaugural event two years previously.

Comedian John Vlismas was the host; the stage featured red-backed leather sofas, couches and chairs with a screen at the back. Listing these fancy features, Styli laughs: “These were big stage production values for us.”

2012’s Gathering reflected a new shift in the way Daily Maverick saw itself, Styli says. “It focused our editorial on politically dominated current affairs whereas before, up until that point, I guess we had ambitions of being more of a general news site.”

One of the speakers at The Gathering that year was a Marikana miner, Bhele Dlunga, who was interviewed on stage by Marinovich and spoke of the harrowing police brutality and intimidation he had experienced.

“It was an incredible moment, you could hear a pin drop,” says Styli. “Even though we were translating it, everyone was hanging on every word… the pain of what happened.”

Dlunga was one of 17 miners subsequently charged with the killings of police officers, Lonmin security officials and some mineworkers at Marikana. About to stand trial in 2017, Dlunga was shot and killed in mysterious circumstances. “Miners are being assassinated in Marikana, again,” reported Greg Nicolson for Daily Maverick.

Dlunga’s testimony made the 2012 Gathering feel particularly important, Styli says. “A lot of the stuff makes you feel angry and a lot of it makes you feel sad, and I think that’s always what we wanted to do, to create these meaningful experiences in the event space.”

“Enter the Daily Maverick WhatsApp group. Its name? “Carpe DM”, of course.”

The 2012 Gathering delivered more than just meaning to the Daily Maverick bunch. It’s where they also first discovered WhatsApp as a team communication tool (or curse, depending on who you ask). Enter the Daily Maverick WhatsApp group. Its name? “Carpe DM”, of course.

With a decentralised newsroom and the bad habits of iMaverick still in play, the Carpe DM group would prove to be a significant instrument in fostering a sense of unity and keeping the Mavericks in touch – and often at play.

It’s where, even today, not a birthday goes forgotten and no great piece of work goes unpraised. It’s a forum equally used for critical debate and typing-cat memes. Information is traded, support (when needed) is dispensed and banter flows. Those new to Daily Maverick often find the stream of text – paired with the sometimes confusing nicknames bestowed on its staffers – bewildering.

Greg Marinovich, as previously mentioned, is “Bokkie” thanks to a term of endearment from his wife. His namesake Greg Nicolson is often referred to as “Jack”: a joke lost in the mists of time, relating to actor Jack Nicholson. Managing editors Janet Heard and Jillian Green are known collectively as the two-headed hybrid “Janellian”. Some writers go only by their surnames, for no apparent reason: Grootes and Poplak are one-name wonders, like Madonna.

The WhatsApp group operates somewhat like a chaotic and very informal online office. As it turned out, this virtual meeting place would be the saving grace for the team at the ANC’s 2012 conference in Mangaung. The ANC had tricks up its sleeve, but Daily Maverick had Carpe DM … and Ranjeni Munusamy.

Mavericks in Mangaung

In the conference held in the city still known as Bloemfontein, always-the-bridesmaid-never-the-bride Kgalema Motlanthe’s camp would be trounced and Zuma and his allies returned to the ANC’s top leadership. The ANC’s media staff also did their best to trounce the media, with what Branko believes was one of the most cunning media strategies he’d ever encountered – but the ANC hadn’t counted on the 13-person Daily Maverick crew.

Taking place on one side of the University of the Free State’s sizeable campus was the main conference event. At most occasions of this stature, one would expect the media centre to be close to the plenary tent – except, in this instance, the ANC’s spin-doctors had spotted the value of corralling the gathered press corps into a dedicated media tent on the far side of the site. Even reporters on deadline had to traverse a two-kay trudge-fest across campus to the main show, and back, for their every commute.

“The ANC’s masterstroke? A free drinks bar in the media centre. When this strategy seemed to bear fruit, another free drinks bar mysteriously popped up on the opposite end of the media centre.”

The ANC’s masterstroke? A free drinks bar in the media centre. When this strategy seemed to bear fruit, another free drinks bar mysteriously popped up on the opposite end of the media centre.

“Once you’re drunk, you’re not exactly interested in working, never mind walking two kilometres to some press conference,” says Branko. “Some news crews got so sloshed that a guy from ANN7 started attacking Sipho racially. At the end of Mangaung, we were the only ones standing – after blowing 10 grand on energy drinks and coffee.”

The net result of the Daily Maverick team’s caffeine-fuelled counterattack? Breaking almost every major news story at Mangaung. And not falling for the red herrings.

A few stories got past the team. News that long-term Cabinet member Trevor Manuel would no longer accept any ANC candidacy nominations was broken by veteran journalist Zubeida Jaffer. Fake news that Cyril Ramaphosa was pulling out of the deputy president contest was “broken” by Independent Newspapers’ Piet Rampedi.

“Everything else was us,” Branko says. “At some press conferences, we were the only people there. And Ranjeni did so unbelievably well – it was her natural habitat, this. That’s what you get for 20-odd years of observing the ANC, and a great brain. When Ranjeni was on fire, she was absolutely unbeatable.”

As Mangaung played out, it was clear that Daily Maverick was solidifying its status as a serious news-breaker. But because Branko and Styli still had an uphill climb in making the publication financially sustainable, the conference was also a chance to trial another idea.

“When we realised iMaverick was not going to do the trick, we started looking around, and I had the idea of doing ‘NewsFire’, our answer to a wire agency, because Sapa was breaking down,” says Branko. “We approached Michael Jordaan with the opportunity to invest in this expansion opportunity and he agreed in time for us to launch NewsFire as a free wire service at the conference.”

There were some notable successes: among them, a now-iconic photograph taken by Marinovich, which captured Kgalema Motlanthe’s realisation that his leadership contest was in ruins. In the image, a resigned-looking Motlanthe flashes a rueful V-for-victory sign. The picture became one of the defining images of the conference, and was used by newspapers throughout the country with a credit to Marinovich and the NewsFire endeavour.

But the wire service was short-lived. “We didn’t get enough interest from our competitors to subscribe to NewsFire in the end,” Branko says. “And as we predicted, soon after that Sapa fell apart.”

Today there is no homegrown news agency of note in South Africa. Branko’s summary: “As usual, we had the correct analysis of what was going on, we were ahead of time, but we didn’t have enough money to push our product properly. We couldn’t raise more funding for it, and it folded early in 2013.”

Nonetheless, a star performance at Mangaung had confirmed to the team that they were on the right path. But coming so soon after the trauma of Marikana, it was hard to summon a winning feeling. They were exhausted. Driving home from the conference, extremely unwelcome rumours began to circulate.

“We got the news that Nelson Mandela was very sick,” Branko says. “He had had gall-bladder surgery, and apparently they had struggled to wake him up. We were so tired at that point, we thought we were going to collapse. We were falling apart. No sleep for seven days. We had spent R10,000 on energy drinks, for crying out loud!”

The death of Nelson Mandela was guaranteed to be the biggest story for South Africa in decades. It would have international impact. It was also a day most South Africans had long dreaded, and for the Daily Maverick team driving back to Johannesburg, that dread was compounded by sheer exhaustion.

Says Branko: “We were done. The whole team selfishly begged Madiba not to die at that moment, because, if he’s dead, we’re dead, basically. We simply didn’t have the energy to report on him.”

Although the source of the information was impeccable, the decision was taken ultimately not to run a story at all.

“Our energy levels aside, the whole thing felt gory,” says Branko. “They couldn’t wake him up for four hours after surgery. We didn’t want to be sensationalist, because we didn’t know what was going to happen with him. There was still a chance he could rally, and – mercifully – he did.”