A rag to be reckoned with

Going live on 30 October 2009 to a humble audience of only a few hundred readers, Daily Maverick’s first week headlines proved a harbinger of the kind of news the online-rag-that-could was planning to dish up to faithful Maverick and Empire readers.

From the moment Daily Maverick’s writers left the starting block, they were biting their thumb at corruption and its cast of grandstanders.

“Sexwale wants to root out corruption (sound familiar?)” Tim Cohen’s first feature asks. Cuttingly farsighted in his early assessment of the dark days ahead for our fiscus, Cohen fingers the Department of Communications to emerge as the “first institution to mount a direct assault on the authority of the Finance Ministry, proposing in legislation a direct tax which would double the SABC licence fee”.

It’s pre-World Cup days, these, and South Africa is still just about hanging on to its reputation as the world’s rainbow darling, but in Tim’s appraisal then-finance minister Pravin Gordhan was already facing off with the shadow state’s attempts to bully taxpayers into bailing out floundering parastatals.

Eagle-eyed and feisty, fledgling Daily Maverick instantly landed as an irreverent new voice that did not waver in speaking truth to power: a signature that would come to define its brand of reporting.

Compared with the Rainbow Nation bubble that would, in a couple of years, burst within a few decibels of the Krakatoa Volcanic Eruption of 1883, the news emerging from South Africa at the end of the new millennium’s first decade would be innocuous. These were the days when the Congress of the People could still make a front page: “Boesak resigns from Cope, but welcome to return ‘home’”.

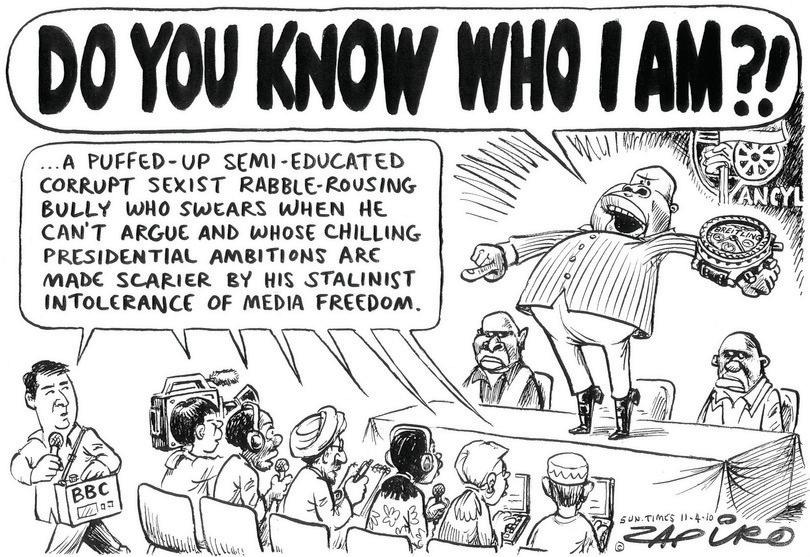

But already there was one politician hogging the spotlight. Julius Malema was driving much of the news agenda that year, and Daily Maverick followed him all the way.

It’s easy to forget that when he first arrived in the communal eye as leader of the ANC Youth League, Malema was primarily received as a source of ridicule. He was at the helm of a body which had long since ceased to be viewed as an important training-ground for future ANC leaders, and instead had become a delinquent kindergarten for overgrown political toddlers.

After all, while the ANCYL maintains some valuable voting power at ANC conferences, to the general populace of South Africa they were for many years just the noisy brats of absentee parents. The (incorrect) assumption was that they were the ANC’s problem, not South Africa’s. Someone once likened them to a public feedback loop – a brash barometer the ANC could use to see how the public reacted to ideas under the protection of another unit that they could quarantine, if necessary.

Malema had inherited the reins of the ANCYL from Gupta-linked lackeys Malusi Gigaba and Mr Fairweather Friend, Volte-Face Fear Fokkol himself, Fikile Mbalula.

And Mbalula as ANCYL leader seeded some of the ground for Malema: turning up the heat at the 2007 Polokwane conference that thrust Zuma into power, making comments that hinted at violence. But in terms of impact, Mbalula was a mere curtain-raiser for the main act of modern ANCYL presidencies when his successor Malema stepped up to the mic.

Loud and brash, Malema was initially written off by many as just another blowhard equipped with a deeper baritone than the rest. His incendiary comments and treatment of journalists (“Bastard! Bloody agent!”) sparked disapproval and bemusement. But his much-publicised devotion to the erstwhile president made it easy to write him off as just another useful Jacob Zuma meat-puppet.

Ten years later, it’s now possible to see more clearly just how seismic Malema’s impact has been.

In much the same way that the US has struggled to get to grips with the tornado that is Donald Trump and his scant regard for the norms of what is presidential or decent, Malema playing by his own rules has carved out a new paradigm of how South African politicians could behave.

The Malema Show. Like moths to a flame or rubberneckers to a cash-in-transit pile-up on the N1, we – the media and the public in general – could not look away then, nor can we now. Despite the massive damage caused by Jacob Zuma over the last 10 or so years, for Daily Maverick, Malema was the bigger newsmaker in the early days.

In increasingly rare public appearances, withdrawn, dull, unresponsive and a monotone script reader, Zuma, while Machiavellian in his backroom dealings, offered much less than Malema by way of audacious quotes. And, for Daily Maverick and other media outlets, those verbal nuggets played a major role in their coverage. How could you ignore Malema?

Branko says, “It was all Juju. He was providing soundbites every day. The reality is that he was there all the time, Daily Maverick was a daily publication turning to politics, and the engine behind our coverage originally was not Zuma. It was Malema.”

For Branko, watching one early Daily Maverick contributor in particular interact with Malema made it clear just what a star he would turn out to be in Branko’s editorial firmament.

“At the first press conference that I went to as editor of the publication in 2009, I was sitting next to Stephen Grootes – who in those days was a 702 reporter, and was writing for us. I was there as Malema was threatening him, that he was going to talk to Stephen’s bosses and get him fired. At that moment, as Malema was threatening him, Grootes just looks at him without any emotion and asks him some more questions. It was brilliant to watch this complete, proper reporter. There’s a reason Grootes is so good and so beloved as a radio journalist. It’s not about him. He’s got almost no ego. His job is to report what happened.”

For Daily Maverick, reporting what happened meant reporting on what Malema said, even if they knew that what he was saying was often a blatant diversion from other crises he did not want to discuss. It’s an odd relationship when you know that someone as reckless and calculating as Malema understands how to harness the media to his own ends, but that ignoring him is simply not an option. But, as Malema has discovered to his detriment over the years, while a free press may give you coverage when you want it, they also report on you when you least desire it.

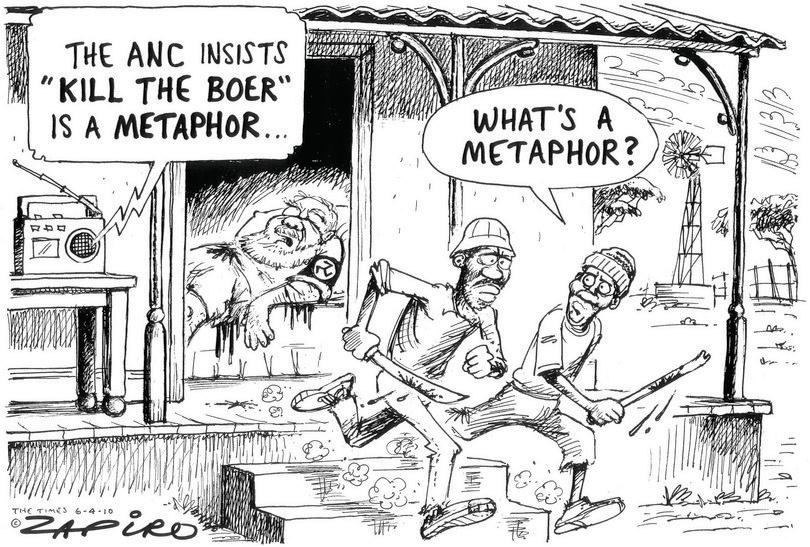

Branko says, “When investigations started into some of Malema’s business deals, like the On-Point/Ratanang Trust scandal, the next thing Juju does in March 2010, is he goes to universities and sings ‘Kill the Boer.’ The whole country starts talking about that and forgets about his business deals. In April, right-wing leader Eugène Terre’blanche was killed on his farm.”

Grootes, who has keenly followed the arc of Malema’s career, has been in the pound seats for each and every twist of what has been a contemporary political drama unlike any other South Africa has seen. Most notably, Grootes has witnessed a distinct evolution, as Malema has transformed from ANC darling to ANC bad boy and finally, ANC bête noire.

Grootes says: “I would say from around 2010 onwards, but really around 2009, there was a Julius Malema 1.0, and I spent my life reporting on him as leader of the ANC Youth League, because he was very good at defining the narrative. I remember coming out of an ANC Youth League conference having spent the weekend there.”

In Grootes’ recollection, “two quite bizarre things” happened at that conference.

“It was during a time when people were trying to make the Springbok rugby jersey cool, and so at work you were sort of expected to wear it. So I wore mine to the ANC Youth League conference and my white friends asked, ‘Are you insane?’ I said it would be fine – and when I got there, I was accosted by three ANC Youth League Limpopo guys who were wearing their Springbok jerseys and we went and had a picture together, because that was the power of the brand. It had shifted, and that for me was a real indicator of a shift.”

But Grootes’ second takeaway from the conference was in stark contrast to the warm-and-fuzzies of the Springbok selfie.

“On Sunday, Julius Malema gave this speech (Ed: about going to war on policy, including the nationalisation of land and mines). The piece I wrote is still online, in which I called him ‘Julius Malema 2.0’, because the next day [Cosatu leader Zwelinzima] Vavi gave a speech against him and that was ‘Julius Malema 2.0 meet Vavi (Cosatu) 2.0’. It was a really interesting thing that was going on. I came back from Julius Malema’s speech with all the sound recordings on a flash drive and I walked into the 702 building at 7 o’clock in the morning and said, ‘I’m going to scare the shit out of the whites this morning,’ because that was essentially everything Malema had said in his speech.”

“Forget the president or the secretary-general – the youth leader of the governing party is driving the narrative of the country. And the media is giving him as much coverage as he can gorge himself on.”

Pause for a moment to consider how weird this is. Forget the president or the secretary-general – the youth leader of the governing party is driving the narrative of the country. And the media is giving him as much coverage as he can gorge himself on. Even by the standards of South Africa’s mad political scene, this was not normal.

Grootes says, “So much of what was happening was being driven by Malema. Take his comment, ‘There is no word in isiPedi for hermaphrodite’, about Caster Semenya, which became this racialised, genderised issue. He was the person you spoke to about these things. He would drive the narrative, and that still happens: journalists will cover an EFF statement long before a DA statement.”

But particularly at the time, says Grootes, Malema was significant not just for his outrageous comments, but because he was “the legitimate face of black expectation and black demands for recognition in what was then still a very white society”.

Grootes adds: “Looking back at how things have shifted, transformation is only just beginning now, but then [racial polarisation] was more obvious, and so the battle lines were drawn in a much clearer way than they are now.”

From his statement that, as the youth league, “We are prepared to take up arms and kill for Zuma”, to the way he fomented support for Zuma around his rape trial with the outrageous suggestion that Zuma’s accuser, Khwezi, had “had a nice time”, Malema proved himself as an incredibly useful tool to JZ’s faction of the ANC. However, as he grew in power, Malema became harder to control.

Nothing to lose: the prime position

From the town-crier to the printing press, evolution within the media world has been constant. But around 2009, it started to feel like the shifts were swifter and more profound than ever before. Digital evangelists declared that the writing was on the wall for print. Across the industry, ad sales were plummeting, magazine teams were getting slashed and whole titles were going under. It was carnage (and of course, it still is).

With Maverick magazine Branko had experienced this first hand and he knew that the future of the media world was in digital. That’s why he did not try to make a comeback in print.

As for Styli, his formative years were not spent in print publishing, so there were no good old days to reminisce about. But it was immediately clear to him that his new gig in largely uncharted digital waters carried its own perils – and opportunities.

“If I had stayed in tech or the investment banking space, I would definitely have earned a lot more money for a lot less risk, but I also think my mental health would have suffered,” Styli says now. “When I was young, I knew that I wanted to become a chartered accountant, and then when I got the qualification I had this big sense of, ‘now what?’ It takes seven years to get there and all you are focusing on for those seven years is just qualifying. That’s why I went to London to earn some hard currency, as a lot of people did, and I guess to mess around too and enjoy the big city life. I was contracting, getting good money with not a lot of challenging work.”

When Styli returned to South Africa after three-and-a-half years abroad, he did so not just out of a sense of personal obligation but also because there was a new entrepreneurial spirit in the air – and he wanted in.

“The 2010 World Cup was happening, there was a lot of optimism around South Africa, the new-President Zuma effect. I came back a few years before he had been elected and caught the tail-end of the Mbeki era, and the reckoning that half a million people had died or were dying because of the ARV situation. There was almost an ‘anyone but Mbeki feel’ to the national mood. Nobody could be worse.”

Styli shakes his head ruefully.

“Jesus, we were wrong.”

The media landscape that Styli was introduced to in 2009, however, was one out of step with the national sense of renewal and positivity.

“I’ve only really known media in South Africa as being on a precipice. Huge retrenchments, despair and a dark mood. At Daily Maverick there was always this cycle of begging, borrowing and trying to raise equity in a place in which it is notoriously difficult to raise funding for any venture, let alone a digital media effort.”

It was a time when the prevailing media wisdom still held that publications should reserve their best quality journalism for print, where the money lay, and use the digital space as a receptacle for more disposable content.

“Because of that, the only guys who were unreservedly jumping into digital were the News24 team. Because the revenue streams in the digital economy weren’t there yet, they were determined to be well-placed when it arrived. And use those eyeballs to generate revenue off their eCommerce platforms. As such, the ruling model became getting as many page views and putting as many ads on a single page as possible. Back then, it felt as if the approach was: ‘What is the lowest cost at which I can produce a page which I can monetise with as many ads as possible?’ It wasn’t really a formula that lends itself to investing in quality journalism.”

What Daily Maverick had going for it was that it was lean and nimble, and it had nothing to lose. Most competitors, with their established print dominance, their ad sales, mag sales and subscriptions, had more at stake – and so reacted slower to the digital wave insofar as it meant putting out quality long-form content online.

Daily Maverick was just as clueless as to what would work and what would not. But they didn’t have a print operation to protect and were more willing to take on risk. It was all in the name.

Initially, the idea of a news website called “Daily Maverick” raised eyebrows. Would anybody take it seriously with that name? Would the jokes that it was linked to Cape Town’s notorious strip club Mavericks ever end?

But the notion of a “maverick” spirit was something Branko held dear. He says the name came to him in the shower one Sunday morning – the place where he routinely receives his best inspiration.

“The idea [of a maverick] is kinda inspirational and aspirational,” Branko says.

“But also, turns out it’s the best name for a revolution. It conveys a clear sense of purpose and a clear mission. Challenge the establishment. Challenge the commonly accepted truths – which many times are lies.”