The starting pistol

Valentine’s Day 2013 was always set to be a busy one for South African journalists: not because of their exciting love lives, but because the country’s Number One had inconsiderately scheduled the annual State of the Nation Address (SONA) for that same evening. The joke doing the rounds was that President Zuma had deliberately chosen Valentine’s Day for the occasion so that he wouldn’t have to decide which wife to spend it with.

But early that morning, things took an unexpected twist – as Rebecca Davis would recall in a retrospective piece she’d pen the following year, “Pistorius: Anatomy of a story that gripped the world.”

“At 8.13am, the first email went out to the Daily Maverick editorial list. ‘Have you seen this?’ I wrote. ‘Oscar Pistorius allegedly shot dead his girlfriend this morning thinking she was a robber.’ Accompanying the mail, a link to one of the first notifications in the news, carried by Afrikaans daily Beeld. ‘Please be on it,’ Daily Maverick editor Branko Brkic emailed me back. ‘We need to cover it, unfortunately.’ I sighed, because this was not part of the day’s plan. At 10am I was supposed to meet my colleagues to do some planning for our SONA coverage. I regretted bringing it to my editor’s attention.”

Rebecca remembers being stationed in Parliament for SONA, but all the while keeping one eye on the Pistorius story. “I had a feeling it was going to blow up massively,” she says. “There was just something about the circumstances that smelled seriously dodgy: the very first reports had it that he’d killed his girlfriend – whose name we didn’t even know – mistaking her for a robber, but only a few hours later this very tough-looking female cop got in front of the cameras and shut that narrative down, saying they were investigating a murder.”

It was unthinkable. At the previous year’s SONA, Zuma had even singled out Pistorius for special praise in his speech: “Our star performer, Oscar Pistorius, has set the standard for the year by winning the 2012 Laureus Sportsperson of the Year with a Disability Award.”

Rebecca wasn’t the only one with an eye on the big story of the day. She says: “All the politicians at SONA that year were abuzz with the news too, since they’re only human. I vividly remember bringing the Pistorius news up with the now deceased but much-missed IFP MP Mario Ambrosini, who summed up his take on the matter with two words: ‘HANG HIM!’ (Best said to yourself in Ambrosini’s thick Italian accent for full impact).”

This was set to be much more than a tragic twist in the tale of a global athletics idol. Although Pistorius was still to be proven guilty, the shooting spoke to the hearts and minds of a country already staggering under the blows of domestic violence and femicide. Less than two weeks previously, a usually violence-desensitised nation had reeled in horror at the news of the brutal rape and disembowelment of 17 year-old Western Cape teenager Anene Booysen.

Sitting in Parliament’s media centre, Rebecca wrote her first take on the Oscar Pistorius story. “The discovery that a national hero and global poster-boy for inspiration may also be a murderer is devastating. But we cannot allow Pistorius’s status to prejudice our response to what seems – based on scant available evidence – like a gruesome act of domestic violence. If this is what it was, to downplay it would be to betray Anene Booysen and countless others.”

She concluded with a plea to focus on the wider issues at stake: “In any other country in the world, a death like Steenkamp’s would provoke a vigorous national conversation about gun ownership. In South Africa, that’s unlikely to take place to any meaningful extent: too many citizens exist in a siege mentality, and too many people live in fear. But even if we’re not going to talk about guns, we have to keep talking about violence against women,” she wrote.

“We have to acknowledge that the problem pervades every echelon of South African society: that it touches the leafy estates of Pretoria as well as the construction sites of Bredasdorp. We have to work on developing alternative masculinities: ones that prize virtues other than being able to run the fastest or hit the hardest. We have to do these things now. It is literally a matter of life and death. For Anene Booysen and Reeva Steenkamp, it’s too late.”

Rebecca had just cemented herself as Daily Maverick’s lead Pistorius reporter: something she would occasionally lament as the story unfolded month after month. Pistorius wasn’t the only person who fired a weapon on that fateful Valentine’s Day: Rebecca had also, magnificently, shot herself in the foot.

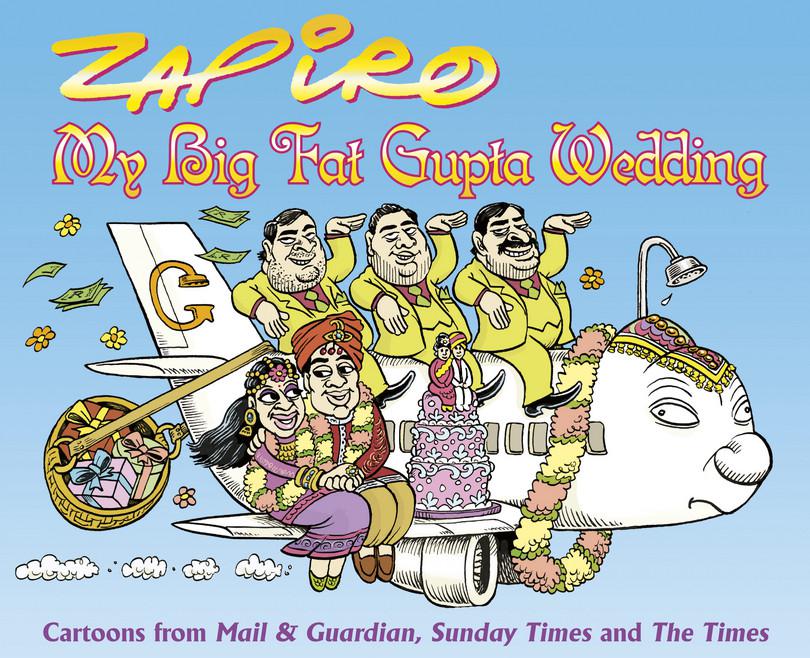

The Guptas have landed

April, month of fools and pranks, brought the first inklings of a scam of monumental proportions perpetrated on an entire country by a single family. The Gupta brothers had appropriated the Waterkloof Airforce Base to welcome a Jet Airways airbus ferrying 217 wedding guests from India.

They’d used a National Key Point as a taxi rank for pals attending a Gupta family wedding – and nobody could understand how it had been permitted. Writing for Daily Maverick, Khadija observed: “Heads will have to roll to absolve the Zuma administration of any blame in the Gupta plane saga, but while government scrambles over determining exactly whose heads those must be, the proximity of the Guptas to South African government officials does merit scrutiny as well.”

Just weeks afterwards, in May, Daily Maverick’s political oracle, Ranjeni, issued a chilling warning in a near-clairvoyant analysis of the Gupta incursion.

“A persistent question following the Gupta jet being allowed to land at Waterkloof Air Force Base is ‘How could this have happened?’ The answer is rooted in a debacle in the Department of State Security two years ago, when the former intelligence heads tried to warn government that the Gupta brothers posed a possible threat to national security,” she wrote.

“But their investigation was stymied, leading to them losing their jobs. Therefore the phalanx of Cabinet ministers and senior government officials now claiming to be mystified about the security breach need to look no further than the State Security Minister Siyabonga Cwele and President Jacob Zuma.”

This was the moment South Africa’s own Rasputins alighted in the South African consciousness as a cloak-and-dagger clan all too comfortably nestled within the state’s sphere of influence. While in Mangaung the previous year, Branko had already become aware of how much clout the Gupta family had amassed since launching the now-defunct New Age newspaper in 2010.

“You can say 2013 was the year the Guptas graduated. We’d kind of seen them as low- to mid-level bloodsuckers until that point. But then we walk into the plenary hall at Mangaung and the three brothers, Ajay, Atul and Tony, were sitting next to Zuma’s wives. That’s when I thought to myself, ‘Holy fuck. These guys are big.’”

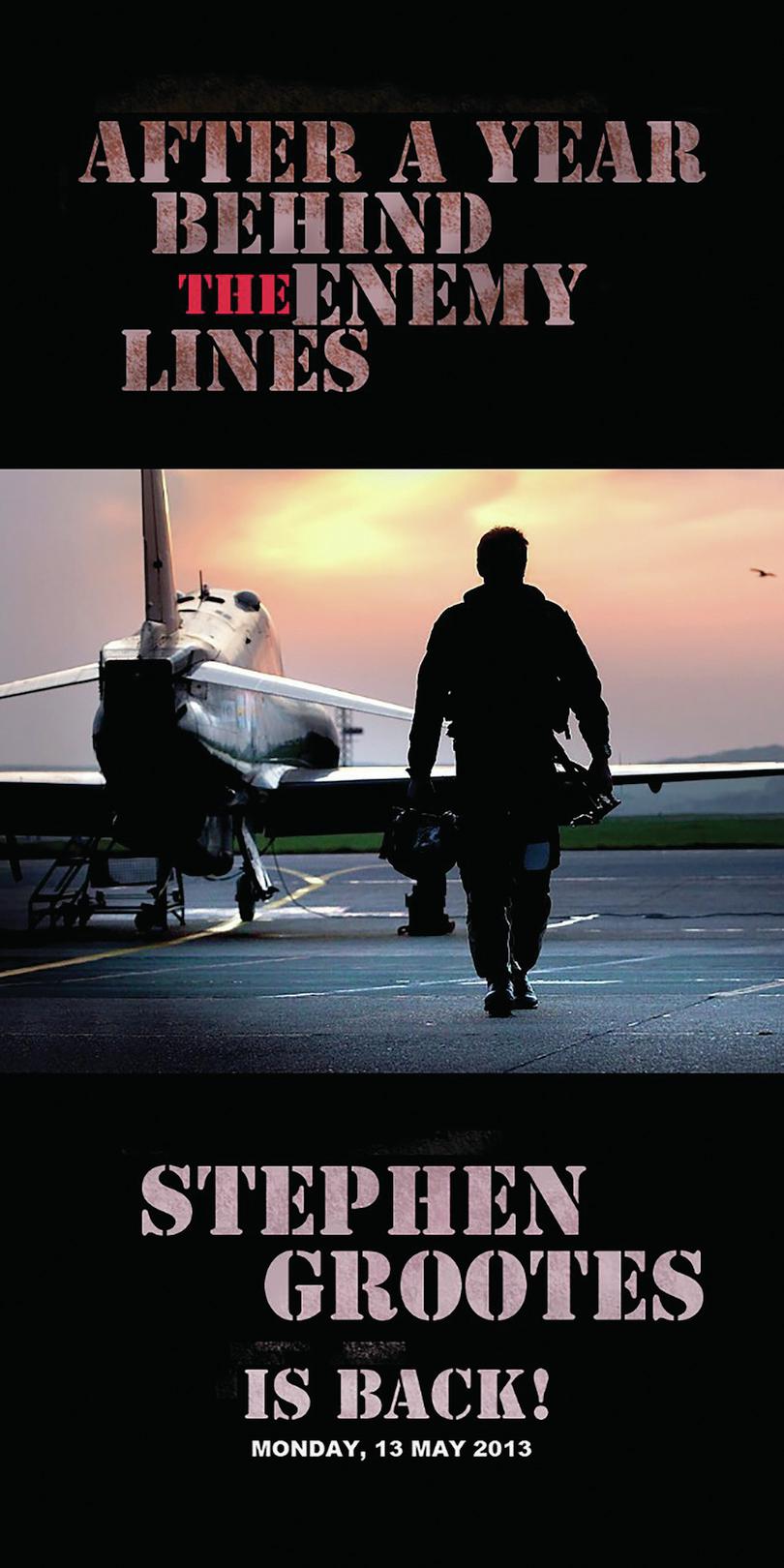

Behind enemy lines

After a year’s hiatus with a rival publication, Stephen Grootes made his own military-style landing off a fighter jet – metaphorically speaking – to rejoin the Daily Maverick tribe around the same time.

“Grootes had asked for coffee. Of course I knew what he would say. He was so sweet and just said: ‘Would you please take me back?’” Branko laughs mischievously. “He’d been in sheltered newspaper employment; realised how good he’d had it with us, I guess, or relatively speaking, at least.”

Branko couldn’t resist having some good-natured fun at Grootes’ now former employers’ expense. “After a year behind the enemy lines, Stephen Grootes is back”, read the headline on a Photoshopped image published on 13 May, depicting the political journalist emerging from a fighter plane.

The two would-be comedians decided on a further plan to advertise the hire on Twitter. Grootes tweeted to Branko: “Hello @BrankoBrkic, how are you?” Branko, fingers at the ready, replied “Fine…are you missing us?”

“Yes, I am actually.”

“Would you like to come back?”

“I would love to come back!”

“Will you write a piece for us this Sunday?”

The repartee continued in Stephen’s comeback feature. “So, it’s been a while. One year, one month, two weeks and three days to be precise [that long?…. We really hadn’t noticed – Ed]. In that time my life has changed slightly,” Grootes wrote . “The kids are less small, louder, and most frighteningly, more mobile. My wife is, of course, lovelier. My iPad has a few more dings in it (journalism being a dangerous and exciting field), the keyboard a little more tattered. I myself am a little older, greyer, and, dare I say it, stouter [well, we didn’t want to say, but… – Ed]. But enough about me. What else has changed in our wonderful Republic of South Africa?”

South Africa being South Africa, Grootes didn’t have to look far for a story that needed telling.

Some 18 months after virtually every single commentator and media house, including Daily Maverick, had nailed a coffin into the apparent death of Julius Malema’s political career, he was officially back. Grootes gave the first of countless takes on the newly launched Economic Freedom Fighters that would, just six years later, be the third-largest political party in both houses of Parliament.

“In a country as complex as ours, the number of voices matters. Everyone likes to feel they at least have been heard, even if they have been outvoted. Extremism can creep in when people feel they don’t have anyone looking out for them. It’s important to keep people inside the system, rather than outside it,” he suggested. “And when Malema and Red October grab the spotlight, you have to ask yourself if this is the side-effect of our move to what will probably become a two-party system in the end.”

Rules of retraction

There comes a time – in some cases, many times – in the life cycle of any news organisation when it’s necessary to fall on your sword, hold up your hands and admit that things have gone badly wrong. That day came for the first time for Daily Maverick in May 2013.

The source of the problem: an article by veteran investigative reporter De Wet Potgieter, headlined “Al Qaeda, alive and well in South Africa”, published, ironically, on the same day Grootes arrived back, 13 May 2013. The story claimed that a local family maintained close ties to terrorist group Al-Qaeda, and that South African intelligence operatives had failed to properly investigate their activities.

Potgieter’s article, published prominently on Daily Maverick, caused an immediate stir – unsurprisingly, given its alarming claims. But concerns about its veracity also began to grow in volume and intensity. The death-knell for the piece came when GroundUp, a gutsy new website, published a convincing rebuttal to Potgieter’s reporting, suggesting that he had chronicled little more than untested allegations. GroundUp concluded that “Potgieter’s article should not have met the Daily Maverick’s standard for publication.”

Weeks before, Branko launched an internal investigation, and realised that the story had big holes. There was nothing for it. Branko had to face what he described, then and in hindsight, as the worst moment in his career.

Weeks before, Branko launched an internal investigation, and realised that the story had big holes. There was nothing for it. Branko had to face what he described, then and in hindsight, as the worst moment in his career.

“Going through an internal investigation and the realisation that one was wrong is an experience I don’t particularly wish to repeat in this life,” Branko wrote in the story’s official retraction – “The most bitter pill of all: Your own failure” – on 19 June. He added: “Let me state clearly: I am personally responsible for this failure,” drawing his concluding insights from the 1941 film Citizen Kane.

“Orson Welles portrays Charles Foster Kane, the crusading editor who, as the first edition of his newspaper rolls off the presses, pens his famous declaration of principles: ‘I will provide the people of this city with a daily paper that will tell all the news honestly. I will also provide them with a fighting and tireless champion of their rights as citizens and as human beings.’

“Sadly, by the end of the film Charles Foster Kane has lost his way. Our promise to you, the reader, is that as much as is humanly possible for us to do, we, the editors and journalists of your Daily Maverick, plan never to lose ours.”

Styli remembers the time as one of extreme emotional and financial cost. “That story was a pressure cooker once we published, and it almost bankrupted us. It angered sections of the Muslim community and it turned pretty nasty, pretty quickly. Off the back of that, we initiated a full investigation into the story using a law firm and ultimately it became the only full retraction we’ve had to make in 10 years. It took us an age to pay off the legal fees for the investigation, even though we never actually got sued. It was a proper lesson in the potential dangers of investigative journalism.”

From the very beginning, Branko let the debate rage on Daily Maverick’s own platform. This included a right-to-reply comment from members of the Muslim community of South Africa, civil society at large, the incorrectly implicated family – and, crucially, Potgieter himself, who on 19 June published an opinion piece called “My world, turned upside down”.

The piece explained how he came across the investigation, the intentions of the investigation and the consequences of it being published. “As five weeks have passed since we published the story, there has been no action from the authorities, and the promised second wave of evidence has not been delivered. With a benefit of hindsight, should I have submitted the story at this stage of investigation? Definitely not,” he admitted. “I was caught up in the twilight realm of a power play in the intelligence world, and I have paid the price.”

Life became “better after we owned up and apologised”, says Branko, but not before Potgieter’s story contributed to “raising eyebrows” within the US intelligence sector.

With the wounds of the Al-Qaeda story still fresh, Branko tackled a retrospective piece in October, looking over Daily Maverick’s “first four tempestuous, madly eventful years”.

While acknowledging the only story Daily Maverick had to retract in its first four years in business, Branko also highlighted what the fledgling newsroom had done right. “Today, we think it is safe for us to say that Daily Maverick is part of SA’s mainstream media. Our voice is heard far and wide, and our journalists celebrated among some of best in the country,” wrote the editor-in-chief. “And yes, we wish we could cover many more subjects than we do, and we wish we could give you a proper wall-to-wall experience. We’re not there yet, but it will come.”

As part of their effort to cover more, Branko brought on veteran journalist and occasional comedian Marianne Thamm. Marianne started her career as a crime reporter at Cape Times in the ’80s. Initially she joined the Daily Maverick team part-time as assistant editor while working on a book, and Marianne now admits to somewhat mixed feelings about that gig: “We would edit and sub about 30,000 words or more a night. I am not a natural editor. I absolutely hated it…”

Once Marianne had swiftly jumped ship to join the full-time writers, her experience in crime reporting – and her general journalistic nous – would prove invaluable to the Daily Maverick team. Managing editor Janet Heard explains: “She’s creative as a being, which makes her writing stand out. People take notice. She doesn’t just state the facts; she writes with flair and creates a narrative that is readable, compelling. She has insight and institutional memory to connect the dots to the story, which is so essential to explain events. Marianne goes beyond the surface of a crime story. It’s layers of complexity and intrigue.”

Straight out of the starting blocks, Marianne focused on Jackie Selebi and his questionable parole. It was the inaugural airing of what would become one of the definitive voices on South African crime for both Daily Maverick and the country. Branko describes Marianne’s hire as “getting a 21-year-old single malt whiskey into an already impressive talent cupboard”.

The chronicles of Nkandla

The then-Mail & Guardian’s investigative unit, amaBhungane, dialled up the heat around President Zuma’s Nkandla upgrades by several orders of magnitude when it published a leaked copy of Public Protector Thuli Madonsela’s provisional report on the matter, “Opulence on a Grand Scale”.

“The findings, even provisional ones, paint a frightening picture of a monarch being showered with opulence. It’s easy to see what inspired the report’s title…”

The presidential palace splurge, argued Alex Eliseev for Daily Maverick, was of “overwhelming public interest”. And then he proceeded to elucidate exactly why: “The findings, even provisional ones, paint a frightening picture of a monarch being showered with opulence. It’s easy to see what inspired the report’s title,” he wrote.

“To add some punch, we are shown a comparison of how much was spent on security upgrades at the homes of former presidents (R32-million went to Mandela, R12-million to Thabo Mbeki) and are treated to a Zapiro cartoon of Zuma floating in a swimming pool filled with money. Anyone who has so much as driven through Diepsloot or Alexandra – never mind anyone who lives there – would have punched the walls upon reading the contents of Madonsela’s report.”

In the context of growing public indignation at this latest evidence of corruption emanating from the very top of the ANC, author and Daily Maverick opinionista Sisonke Msimang argued in a December column that no leeway should be given in holding to account even the great and the good. Even, indeed, the Father of the Nation.

“Even the ‘good guys’ – leaders like Nelson Mandela and Frene Ginwala – have had their role to play in building a culture of defensiveness, deflection and lack of transparency in the ANC. Zuma is not the ANC’s problem; he is its creation. It has been a long walk to this dark place called Nkandla and the ANC has spurred Zuma on, every step of the way,” wrote Msimang in “A long walk to Nkandla”.

Mandela, Msimang pointed out, had defended presiding Health Minister Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma when she blew millions in taxpayers’ money on playwright Mbongeni Ngema’s ill-advised Sarafina misadventure.

“Months of media questions and official inquiries ensued. The minister was defiant. Initially, she had claimed that the EU was supporting the production of the play, but EU officials denied this outright. Then she suggested that a mystery donor was funding the play. In the end, she conceded that no mystery man would be stepping forward, and the R40- million production costs were paid for by our taxes.”

Lest we forget: “The minister did not lose her job. Instead, she was defended by her party and by her boss. President Mandela told the media to back off and let her do her job. The ANC suggested that the press had been co-opted by pharmaceutical companies that were angry at her stance on drug pricing.”

This policy of loyalty at all costs, Msimang argued, had cost the country dearly. And the model was set by episodes in South Africa’s young democracy such as Mandela’s handling of the Sarafina scandal.

“It was an early lesson in how the ANC would handle misdeeds by its heroes: it would denounce the critics and defend its own regardless of the facts,” she wrote. “The ‘loyalty’ of ANC members – a strength for an organisation that was constantly under siege under apartheid – has been lethal in peacetime. In today’s South Africa the insistence on loyalty before integrity has had a devastating impact on the way the party operates.”

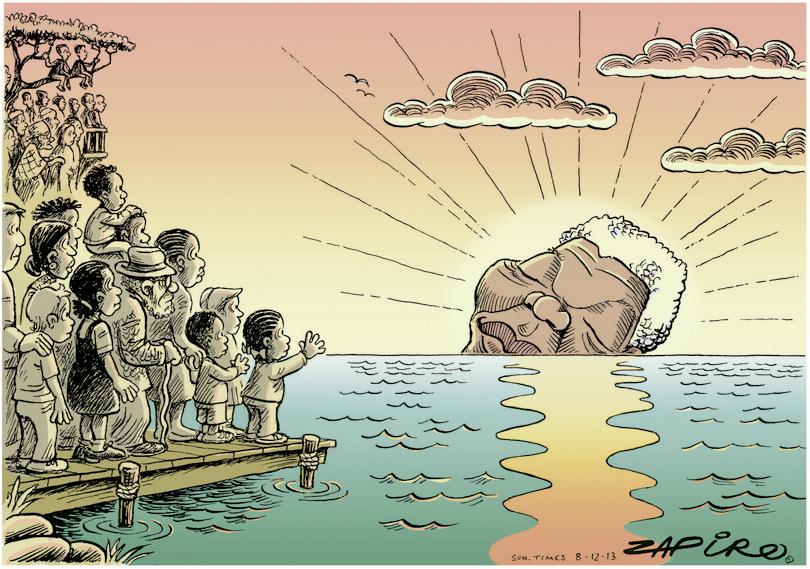

At the end of an eventful year in the cruel, crazy, beautiful country on the southern tip of Africa, the furies of fate weren’t quite done with the locals.

Just hours after Msimang’s story went live, the long walk of South Africa’s first democratically elected president was over.

The death of a lifetime

“Black Pimpernel”, media darling, attorney, treason triallist, ex-husband, husband, father to a complicated family, Father of the Nation, universal teddy bear, political prisoner, freedom fighter, “sell-out”, patron saint of superheroes…

Nelson Mandela lived no ordinary life, and his would be no ordinary death. The contestation over his legacy, the infighting within his family and the question of what his passing would mean to the political organisation he called home: all these tensions began to bubble to the surface long before Mandela took his last breath.

Back in June 2013, during one of the many serious health scares that prefaced the statesman’s death, Grootes had written that “the death of a political figure is in itself a political act”. His piece was “aimed directly” at ANC spokesperson Mac Maharaj, to whom he appealed to allow the media to do their job and to ensure that “the political act of dying is not manipulated”.

Grootes explained that the coverage of Mandela’s dying by the news media would always be complex. Local journalists felt as emotionally attached to Madiba as the rest of the country, while the likes of Maharaj – the political figures tasked with protecting Mandela’s privacy but also feeding information on his condition to a waiting world – had deeply personal relationships with the struggle hero.

“I have huge sympathy with Mac Maharaj at the moment,” Grootes wrote. “I would not take his job this week if you gave me the moon and the stars. Not only do you have to deal with quite literally the world’s media, but you also have to give regular updates on a man you whispered to in the cell next to yours on Robben Island. Whose life story you were one of the first in the world to read.”

Looking back on the period around Mandela’s death now, Grootes says that he is struck by one thing most prominently: the manner in which trust was breaking down between the media and the government, and the ANC and the Mandela family.

“It seems obvious now, but it wasn’t so obvious then, that there was no one really in control of the situation…”

“It seems obvious now, but it wasn’t so obvious then, that there was no one really in control of the situation,” Grootes says. “There are huge reasons for this, and I think it was also because the family was not necessarily getting on with itself. Considering the breakdown in [Mandela’s] marriage with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, it must have been a very traumatic and difficult time for everybody.”

South African journalists, meanwhile, were placed in an odd situation. They were caught between the need to compete effectively with counterparts from around the world in covering what would be one of the country’s biggest news moments in history, and the real distress they felt when contemplating the death of a man who had meant so much to so many.

Grootes put it simply in another piece in July 2013: “We love him. We will miss him. We feel that he has a personal connection to every one of us. Many people have a personal anecdote, that friend who once met him and how Madiba’s kindness shone through at that moment. For many of us, there’s the iconic image of Mandela and Francois Pienaar, or the moment he came out of prison, or his speech as he was sworn in as president. He’s been part of the national fabric of our inner lives for many years”.

The loss of Mandela would be acutely felt, Grootes suggested, because the nation feared losing the “magic dust” he had sprinkled over the land: “It’s because he came out of prison and promised peace. It’s because he had tea with Betsie Verwoerd; it’s because of that wonderful moment when you realised Madiba was actually taller than Francois.”

Critical but stable

The second half of 2013 would bear witness to escalating cat-and-mouse games between state and media as Mandela’s recurring lung infection dispatched him in and out of hospital. There was such chaos in this final act that the world found out from a US television network, not the South African government, that the ambulance rushing Mandela to a Pretoria hospital early one morning broke down en route.

“The former president’s heart had had to be resuscitated … consequently, official guidance on his medical circumstances had been at variance with what had happened to him,” Brooks wrote in his analysis of the incident.

Critical. But stable. Critical. But stable. The ANC’s uniform communiqués seemed to echo in some purgatorial dimension of public consciousness.

Says Greg Nicolson: “We didn’t know if that meant Mandela was going to die tomorrow. Or did he have another five years? There was a whole period of these scares. Always critical but stable. He would go into hospital and journalists rearranged their lives and cancelled two-week holidays abroad. And then it would turn out he was okay again.”

Big media houses had well-rehearsed strategies for the coverage of Mandela’s death ready to execute at a moment’s notice: one local broadcaster termed theirs “the M-Plan”. At Daily Maverick, as always, things were a little less regimented.

“The strategy was, follow Ranj’s lead. She was very much on top of stuff,” Richard Poplak remembers, referring to Daily Maverick colleague Ranjeni Munusamy’s vast political knowledge. “And Branko is a great editor. We couldn’t commit to standing outside Mandela’s Houghton house, but we knew we’d pivot, covering the funeral and the fallout, when we had to. Although we always punched above our weight, we had a much more defined sense of our smallness then. There were no pretentions of getting the numbers we have today.”

Poplak had little patience for the unseemly appetite from the foreign media corps when it came to matters relating to Mandela’s health and death. One London tabloid insinuated links between an alleged looming black-on-white genocide and Mandela’s fading light – six full months before his death – “with chilling echoes of Zimbabwe”. The headline roared: “Mandela’s passing and the looming threat of a race war against South Africa’s whites. As a widow mourns the latest murdered Afrikaner farmer, a chilling dispatch from a nation holding its breath.”

Poplak’s distaste for the international press circus inspired his satirical “Open letter to South Africa from foreign media”.

Dear South Africa,

Please get the fuck out of the way.

Wait, that probably came out wrong. Let us explain.

As you may have noted, we’re back! It’s been four long months since the Oscar Pistorius bail hearing thing, and just as we were forgetting just how crappy the internet connections are in Johannestoria, the Mandela story breaks.

We feel that it is vital locals understand just how big a deal this is for us. In the real world – far away from your sleepy backwater – news works on a 24-hour cycle. That single shot of a hospital with people occasionally going into and out of the front door, while a reporter describes exactly what is happening – at length and in detail? That’s our bread and butter. It’s what we do.

And you need to get out of the way while we do it.

It’s nothing personal. In fact, we couldn’t do this successfully without you. In many cases, our footage is made more compelling by your presence. Specifically, we are fond of small black children praying and/or singing in unison. Equally telegenic are the Aryan ubermensch blonde kids also praying/singing, who help underscore the theme that Mandela united people of all races under a Rainbow umbrella.

Also very important, thematically speaking, are Mandela’s successors. We very much like the idea that your ex-president was “one of a kind”, and that despite his best efforts, the current batch of idiots prove that he was an exceptional presence, sui generis, and we don’t have to worry about someone else like him coming along in Africa ever again. We enjoy your leaders’ bumbling ways, their daft non-sequiturs, the glint of their Beijing-bought Breitlings. That “Vote ANC” truck parked outside the hospital? If that doesn’t speak to moral degeneration of the first order, what does? In other words, this story would lack a tragic arc without Jacob Zuma. May he keep on keeping on.

Then there’s the Mandela’s family. Really, where would we derive our soap-operatic undertones if it weren’t for the infighting and the blinged-up brashness of that clan? We love subtly implying that a saint sired a generation of professional shoppers and no-goodniks. In our biz, we call that “irony”. Makes for great copy.

In fact, we love everything about the country that doesn’t live up to Mandela’s legacy. We will take every opportunity to mention how everything you do flies in the face of everything Mandela would’ve wanted from his people – how you’re basically a nation of under-achieving screw-ups. All of this is fantastic, we thank you profusely for your individual and collective contributions to this essential storyline, and urge you to keep squandering your potential.

But like we said, we’re busy.

We need to be fed, constantly and without respite, big juicy mouthfuls of new information regarding every aspect of the story. Each piece of data, no matter how seemingly trivial or inane, is to us the rich, fatty gravy that we will slather over this one essential fact: the father of your nation is gravely ill, and we’re banking – literally, banking – on his not making it. The geraniums in the hospital planter, beating the chill of winter? Metaphor. Again – no detail too small.

Indeed, you need to brace yourselves. We’re about to engage in the single greatest orgy of industrial-grade mourning porn the world has ever known. Your little country will forever be honoured as the site that made the Princess Diana thing look like a restrained wake for a loathed spinster who perished alone on a desert island. Oh man, this is going to be big.

But that’s then. For the meantime, we need you to behave yourselves. We’re going to be pushy, and we make no apologies for it. This is the news – and news, after all, is the concrete foundation of democracy, a principle Mandela was willing to die for long before he was dying.

Note the solemn tone of our television reports. Ken the funereal passages published in our great papers. At times, the scramble for information may seem like a pursuit entirely free of dignity. But remember that watching a sausage get made can be a grisly process.

We would like to respect the fact that you’re going through a period of great sadness and protracted grieving. But we all need to be grown-ups about this.

So, we ask again, and this time with feeling:

Please. Get the fuck out of the way.

Poplak’s piece spread like wildfire internationally and, unsurprisingly, not every reaction was favourable. Poplak was at the time on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship in Italy.

“I remember the phone going – Ding. Ding. De-ding. De-ding. De-de-de-de-de–. There were thousands of tweets pouring in. I was just like, ‘Switch off the phone. Put it down. Don’t worry about it.’ It was the first time anything I’d written had gone viral. Like proper viral. I felt the full power of the angry, hateful brain of the internet.”

The letter’s notoriety also netted fledgling Daily Maverick its first major recognition when it was read on-air by none other than, yes, foreign media – This American Life, the US-wide cult radio show – in June 2013, Episode 501. It also firmly established Poplak as one of the flagship writers of Daily Maverick.

“Poplak unleashed his own brand of Gonzo,” says Branko. “He’s like the American journalist Hunter S Thompson, only better, because he writes about the facts of fear and loathing, rather than himself. And he understands the poetry of the swearword. Although I do nuke some of it.”

But as with any good satirist, the point that Poplak was making through his letter was a serious one. Looking back now, he says he intended it to “set the tone” when it came to journalism around Mandela’s death.

“It helped us to go, ‘Fuck you.’ This is our space. We’re going to take it from here. Publish really good writing about what this event meant. Especially if people wanted to look at it historically, they could come back to the material, spend some time with it and get a sense of what it was like. We took the historical moment seriously in a culture where ancestral knowledge is considered important but also disappearing at the same time.”

Grootes musters more empathy for the complexities presented by reporting on the South African story as a foreign correspondent. “Foreign media had the usual problem. They had to condense an incredibly complicated story with many strands into something a foreign consumer could understand. I would probably have done the same in their situation,” he reflects.

“Poplak’s piece did put foreign journalists in their place, and it was important at the time. People had come to watch an old man die. As a human being, that is abhorrent.”

But he also acknowledges: “Poplak’s piece did put foreign journalists in their place, and it was important at the time. People had come to watch an old man die. As a human being, that is abhorrent.”

As a journalist, though, the job sometimes requires you to behave in a manner others would consider abhorrent. Grootes admits: “I was one of those [journalists] who had been to his home in Qunu five years before just to understand what the logistics would be when he died.”

Three years before Mandela’s death, Daily Maverick had put in place at least one measure to ensure they’d be ready to mark the statesman’s passing – and it almost caused disaster down the line in 2013.

A Mandela obituary had been written by Kevin in 2010 and saved in the Daily Maverick content system. But a flaw in the system which nobody knew about meant that the obituary was publicly available if you looked hard enough – and it was clearly dated 2010.

Branko shudders in hindsight. “It’s not like we clicked ‘publish’. You could only find the story if you consciously googled ‘Daily Maverick Mandela death’. But someone must have done exactly that. Next thing we knew some person was tagging us on Twitter, asking how on earth we could publish premature news about Madiba’s death – three years in advance?”

Kevin recalls the white-hot rage that nearly jet-packed him into space when he found out he was now That Journalist. “The possibilities here were way beyond career-destroying. If the wind had blown the wrong way, my soul would’ve been cast into the ninth circle of hell. So yes, I was a little pissed,” says Kevin.

To everyone’s relief, the tweet died with an inexplicable whimper, allowing shot nerves a welcome recovery.

The saddest day

Kevin’s tribute – “Rest in peace, Madiba. Thank you for everything” – would find its rightful place in media history when prolonged health problems finally claimed Nelson Mandela’s life at his home in Houghton, Johannesburg, on 5 December 2013 at around 8.50pm. He was 95 years old.

Fifty years ago Martin Luther King called out in hope, “Let freedom ring.” “Freedom” answered his call by walking out of Victor Verster Prison 27 years later – and the world embraced the human embodiment of that elusive concept in Nelson Mandela. The body that nurtured the concept is no more, and now the world again cries out, “Let freedom ring,” this time in tribute. Hamba kahle, Tata Madiba, your long walk is done. By KEVIN BLOOM.

On the morning of Sunday 11 July 2010, the date of the final match of the Fifa World Cup, the BBC broke the news that the international football body had been placing “intense pressure” on 91-year-old Nelson Mandela to attend the closing ceremony scheduled for later that day at Soccer City. According to the report, Mandela’s grandson Mandla Mandela had warned that the outing would be “strenuous” for a man of his grandfather’s age, and urged that the decision be made in conjunction with his medical team. In the event, Fifa was granted its wish – on a bitterly cold Johannesburg evening, the global icon was driven around the pitch in a golf cart, from where he waved to the capacity crowd and the entire world. It would be his last major public appearance.

Rolihlahla Nelson Dalibhunga Mandela died at 95 on Thursday 5 December 2013.

It is nowhere near a stretch to say that the billions who saw him on TV that Sunday in July are now in mourning. A symbol of perseverance, justice, tolerance and compassion to four generations across the globe, he spent the last days of his life with his third wife Graça Machel. The Republic of South Africa, a country he was instrumental in guiding from pariah status to a proud place in the family of nations, will be forever in his debt.

Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 in the village of Mvezo in the Transkei, to Nonqaphi Nosekeni and Henry Mgadla Mandela. His great-grandfather on his father’s side, Ngubengcuka, ruled as the king of the Thembu people, and his father was the principal councillor to the chief of the Thembu. Rolihlahla, meaning “pulling the branch of a tree”, became the ward of Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo after Henry Mgadla’s death in 1927. He was the first member of his family to attend a school, the Wesleyan Mission School near the palace of the regent, where his teacher gave him the name “Nelson”.

Mandela was initiated according to isiXhosa custom at 16, and matriculated three years later from Healdtown, a Wesleyan secondary school in Fort Beaufort. At the University College of Fort Hare, where he enrolled for a Bachelor of Arts degree, he was elected to the Students’ Representative Council. Along with a young Oliver Tambo, he was suspended from the college for taking part in a protest boycott.

Shortly thereafter, Mandela and his cousin Justice, the son of Jongintaba, left the Transkei for Johannesburg to avoid the marriages the chief had arranged for them. Initially Mandela worked as a mine policeman, but in 1941, through the introduction provided by his new friend Walter Sisulu, he was admitted for his articles at Lazar Sidelsky’s law firm. He completed his BA through the University of South Africa, and then enrolled for an LLB at the University of the Witwatersrand (a degree he would finally attain only decades later, while a political prisoner on Robben Island).

In 1943, Mandela joined the African National Congress.

The personal philosophy destined to be forged as a direct result of that momentous decision would be articulated in the mid-1990s, when Mandela wrote in his memoir Long Walk to Freedom: “A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred, he is locked behind the bars of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. I am not truly free if I am taking away someone else’s freedom, just as surely as I am not free when my freedom is taken from me. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity… For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

But, as implied in the title of the memoir, it would be a long road to such wisdom and insight. In 1944, concerned that the ANC old guard had become too conservative and polite to effect any real change, Mandela, Sisulu, Tambo, Anton Lembede, Ashby Mda and others set about transforming the organisation into a more radical mass movement. It was around the political philosophies of these young firebrands that the principles of the ANC Youth League were formed. In 1948, the year the National Party came to power, Mandela was elected the Youth League’s national secretary. By 1952 he was its president, and the key man behind that year’s mass civil disobedience campaign to protest against discriminatory apartheid legislation.

As a consequence, Mandela was convicted of contravening the Suppression of Communism Act. He was given a suspended prison sentence and confined to Johannesburg for six months. Also in 1952 Mandela, having passed the attorneys’ admission exam and with his friend Oliver Tambo, opened South Africa’s first black law firm.

The firm was forced to move its offices out of Johannesburg in accordance with land segregation laws, which only hardened Mandela’s resolve to defy the apartheid authorities. He led the resistance against the Western Areas removals and the introduction of Bantu Education and, in 1955, played a central role in popularising the Freedom Charter. Throughout the decade, he was the victim of sustained repression, repeatedly arrested and imprisoned, and in March 1956 a five-year banning order was enforced on him.

The Sharpeville Massacre of 1960 led to the ANC becoming an outlawed political organisation, and in 1961, along with the other 155 accused, Mandela stood before the court in the mammoth Treason Trial. The trial collapsed under the weight of its own processes, but by this time, having grown disenchanted at the ANC’s philosophy of non-violent resistance, the man from Mvezo had already decided to co-found an armed wing. Mandela was named inaugural leader of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and co-ordinated its first sabotage campaign against apartheid military and government targets.

On 5 August 1962 Mandela was arrested after living on the run for 17 months, and imprisoned in the Johannesburg Fort. While he was there, police arrested prominent ANC leaders at Lilliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, north of Johannesburg. Mandela was brought in to stand as co-accused in what became known as the Rivonia Trial, where chief prosecutor Percy Yutar charged the defendants with the capital crimes of sabotage and crimes equivalent to treason.

Three of the accused – Mandela, Sisulu and Govan Mbeki – decided they would not appeal were they to be given the death sentence. Mandela’s closing statement in court would become an enduring rallying cry in the struggle against apartheid.

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

On 12 June 1964 the judge found all but two of the prisoners guilty and sentenced them to life imprisonment. Mandela was sent to Robben Island, where he would remain for the next 18 years. During his time there his mother and son died, his second wife Winnie was banned and subjected to relentless harassment by the apartheid police, and the ANC became a movement in exile. In March 1982, along with Sisulu, Andrew Mlangeni, Ahmed Kathrada and Raymond Mhlaba, Mandela was transferred to Pollsmoor Prison. President PW Botha offered him conditional release in 1985, in return for renouncing the armed struggle, but he refused, saying: “What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? Only free men can negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts.”

On 2 February 1990, President FW de Klerk reversed the ban on the ANC and other anti-apartheid organisations. Mandela was released from Victor Verster Prison in Paarl on 11 February 1990. In 1991, at the first ANC national conference to be held in South Africa for decades, he was elected president of the movement. He led the ANC through the fraught multiparty negotiations of the ensuing years and in 1993 – with FW de Klerk – was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

It was also in 1993, however, that MK leader Chris Hani was murdered by white rightwingers, an event that threatened to plunge South Africa into all-out race war. Mandela played a pivotal role in pulling the country back from the brink. In a televised address to the nation, he said: “Tonight I am reaching out to every single South African, black and white, from the very depths of my being. A white man, full of prejudice and hate, came to our country and committed a deed so foul that our whole nation now teeters on the brink of disaster. A white woman, of Afrikaner origin, risked her life so that we may know, and bring to justice, this assassin. The cold-blooded murder of Chris Hani has sent shock waves throughout the country and the world… Now is the time for all South Africans to stand together against those who, from any quarter, wish to destroy what Chris Hani gave his life for – the freedom of all of us.”

A year after Hani’s assassination, on 27 April 1994, South Africa’s first multiracial elections were held. The ANC won the vote with a 62% majority, and Mandela was inaugurated as the country’s first black president on 10 May 1994.

By wearing the Number 6 jersey of Springbok captain Francois Pienaar to the final of the 1995 Rugby World Cup, where South Africa were victorious, he galvanised black and white South Africans – if only for a time – around the idea that reconciliation was an achievable ideal.

Madiba, as he came to be known by his grateful countrymen, stepped down as president after one term. He set up three foundations, The Nelson Mandela Foundation, The Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund and The Mandela-Rhodes Foundation, and did not enter full retirement until 2004. At the 2010 Fifa World Cup closing ceremony, the appreciation he was shown by billions of viewers and 90,000 live spectators foretold the legacy that is now his: Rolihlahla Nelson Dalibhunga Mandela was a giant of his era, a supreme example of human fortitude and achievement, a man whose life will serve as a morality tale for the ages.

In addition to Kevin’s obituary, Daily Maverick ran volumes of staff and opinionista writing about the giant spirit that illuminates one of the darkest corners of 20th-century history.

Aftermath

“Celebratory, but sombre”, is how Greg remembers the scenes outside Mandela’s Houghton home on 6 December. “I turned up first thing in the morning. Some journos had been there 12, 15 hours, camping out. The public also started arriving, laying wreaths, bringing flowers, lighting candles. Some people were singing, others were dressed in South African flags,” he says. “There was a unifying spirit.”

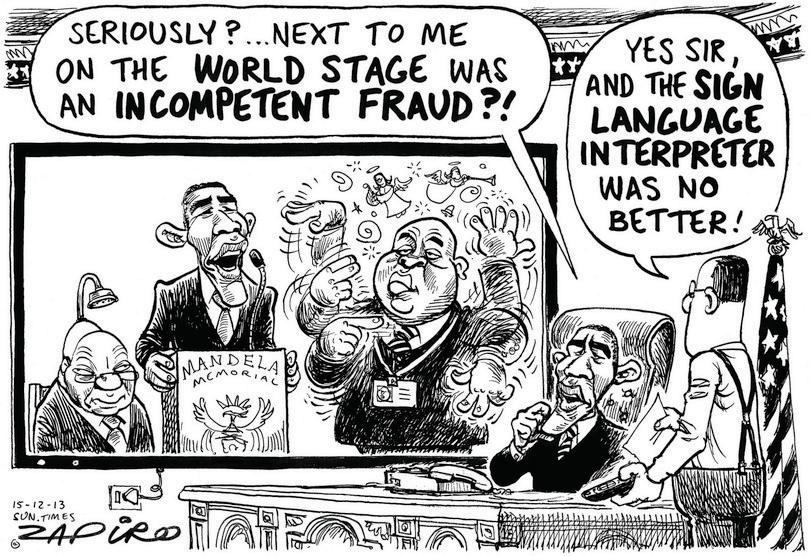

Yet Mandela’s official memorial at FNB Stadium in Soweto on 10 December, and the funeral at his Eastern Cape birth village Qunu, would end up being remembered for factors outside the celebration of his towering life. The headline of one of Ranjeni’s memorial retrospectives summed up what had happened: “When the world came to say goodbye to Madiba and Number One faced ultimate humiliation”.

Ranjeni wrote: “Till the end of time, history will have it recorded that on the day leaders from across the globe joined South Africa to commemorate the life of Nelson Mandela, the heavens wept and the president of the country was humiliated by his people. There is no way to undo that script. The ANC and the state are now in overdrive, trying to ‘contextualise’ and explain why President Jacob Zuma was repeatedly booed during the memorial service.”

This PR disaster for Brand South Africa was, as Ranjeni described it, an “international media narrative” that was “now shifting” to what was “wrong with South Africa that its people would be angry enough to shame their president in front of the world, and whether Mandela’s legacy is being undone by his successor”.

Ranjeni’s report would also highlight the surprise of the presidential office-bearer who, for much of his tenure, appeared impervious to public heckling. Until now. “Zuma looked genuinely startled. He, like everyone else, was caught off guard. And to add insult to injury, his predecessor Thabo Mbeki, who was ejected from office, received roaring cheers. Even apartheid’s last president FW De Klerk was cheered.”

At the time, Grootes wrote that Zuma’s barracking was a turning point – and he stands by that assessment today.

“I still remember the shock I felt. And yes, it was a turning point. Of course it was. It was the first time Zuma had been booed like that. It was the first time a sitting president had been booed. It was the first time a leader of the ANC had been booed,” he says. “It was not the last time, either. Zuma was booed again in that stadium, and then at a Cosatu rally on May Day 2017. And it has echoes in the present. Zuma ducked the inauguration of Ramaphosa precisely because he knew it would happen again.”

The day’s other media sensation came from a sign-language interpreter gone rogue. Memorial signer Thamsanqa Jantjie, tasked with signing the speeches of world leaders including Barack Obama, produced a stream of gibberish that he would later blame on a “schizophrenic attack”.

It was a subject tailor-made for Poplak.

Fog Donkey: The only honest man in a stadium of fools

The Memorial Signer – the man standing alongside speakers at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service at Johannesburg’s FNB Stadium – was called out as a fake, but was, apparently, suffering from a “schizophrenia attack” brought on by happiness. Which begs the question: who, or what, at FNB Stadium on that fated day, was real?

Dollhouse. Petrol. Roadsign. Interested nail. Icon. Much cardboard. Weather. Tile. Tiles. Sheet. Poptart.

POPTART!

I knew that it would not be long before the industrial mourning machine delivered its ruling metaphor, its Neo, its Christ-figure. It took no time at all before we tumbled down the Cartesian rabbit hole, before we found ourselves in a netherworld governed by topsy-turvy nonsense verse, wherein the man flapping his hands meaninglessly was the only man making any sense at all.

His name is Thamsanqa Jantjie. But for one glorious day, he was beyond the banality of names.

Let’s back up a moment. Thousands of mourners filed into FNB Stadium on Tuesday morning, and they had a very simple role to play – that of background colour. As they arrived, the media asked them the usual groaners – Why are you here? What did Madiba mean to you? How far did you travel to get to the stadium? – and they gave the stock answers – Because I loved Madiba. He was bigger than Jesus. I walked 12,000km from Paris over the past three days. These paradoxically smiling, tear-stained faces were meant to provide the backdrop to the proceedings, singing happy songs, singing sad songs, and offering doses of curative African “spirit” for television viewers in Milwaukee and Swansea and Perth.

They had their shot, these good people, and they blew it.

Many files.

Wiper blade. Banana cheese.

Arriving next were our local leaders, who roared over in their motorcades with blue lights flashing and sirens bleating: the signs and signifiers of power in this newly gilded age. The media asked them the usual groaners – Why are you here? What did Madiba mean to you? How far did you travel to get to the stadium? – and they gave the stock answers – Because I loved Madiba. He was bigger than Jesus. I flew in a gold-plated jet from Nkandla to Waterkloof.

To say that this cohort didn’t quite rise to the occasion would be, in fairness, an untruth, because I’m not sure what occasion they imagined they were rising to. Was this a memorial, a campaign stop, a meet-n-greet? Their words were the carefully measured pabulum served to a sick baby, so tasteless and easily digestible that they steamed through the intellect’s digestive tract to emerge as puffs of noisome air, drifting away with the rain.

They had their shot, these good people, and they blew it.

Ducting volume. Me.

[redacted]

Then we had the guests from afar, the super-celebs, the high-wattage smilers. They were here to speak above and beyond the assembled crowd, to measure out small political gestures, to take photographs with the features on their smartphones, to emit enormous words into a cavernous stadium and buff their brands before Clio, History’s muse, who was almost certainly in the stands taking notes. Their words were boxes and boxes of cocoa puffs, served up on the silver of a Versailles dinner set, sugared cereal masquerading as haute cuisine.

The Obamatory was pitched high, so high, in fact, that it laid everything around it to waste, like a Hollywood tent-pole opening a Rwandan film school year-end screening. But what did it all mean? What did it amount to?

They had their shot, these good people, and they blew it.

Mango tank. Sad chair talks.

Jam angel. Fisheries.

Shiny duck. Shiny ducks.

And so it was left to one man to make sense of it all. His job, as I understand it, was to interpret the words on stage for those who hear darkness. It is an ingenious process – by an agreed-upon code, spoken sounds are transformed into gestures, which in turn becomes language. The language is a gesture itself: by providing the deaf with a signer, we are saying that everyone must be allowed to participate – everyone, regardless of disability, is part of the polity.

The problem was simple: the signer did not know the agreed-upon codes. Or rather, the problem is complicated: the signer could not deliver the agreed-upon codes. The signer strode onto stage, stood alongside the most important people in the world, and made gestures that had no meaning to the hard of hearing – that had no meaning to anyone, it turns out, except perhaps the signer himself.

He had his chance, this beautiful man, and he absolutely fucking nailed it.

Biltong!

The deaf are offended, but they should count themselves among the very lucky few – they were the only people being spoken to like adults, like citizens, like humans. The nonsense that travelled through Thamsanqa Jantjie’s hands, conjuring images of Fog Donkeys and Mango Tanks and Moontrumpets and Maximum Coffee Extinguishers, was the best possible language available to describe what has happened to us, what is happening to us, what will happen to us. The deaf saw through his hands the only possible truth – an upside-down gobbledygook of streaming rubbish, a meaningless void of nothingness, a sales pitch selling nothing but the pitch itself.

We will leave aside for the moment the wisdom in placing a schizophrenic alongside the great men and women who spoke for us – a schizophrenic who, if he is to believed, was having a full-blown attack when their empty words travelled into his bustling mind. I believe that the Memorial Signer – not Jantjie himself, but the avatar he represented in that moment – will emerge as the only figure in the stadium that Clio shall reward with historical standing. He is the man of our age, a truthsayer, a sage, a Fog Donkey. The only way to understand all this is through the mind of a schizophrenic. Alternatively, can anyone of us describe the current malaise better than the Twitter handle attributed to him, which noted “Sausage blubber pencil/Prison/Magic lion everywhere”?

The Memorial Signer holds the only flashlight in the midnight dark of the rabbit hole. Follow him, my friends, and no other. For he leads us to the only truth worth hearing: there are no truths at all worth hearing.

At the Mandela funeral in Qunu five days later, the ANC had clearly learnt some lessons. From a certain perspective, the funeral went off without a hitch, with no sideshows to distract from the enormity of who, and what, had been lost.

“It was the end of the greatest love story, the one of Nelson Mandela and his people. His was a life dedicated to political struggle, to the fight for human rights, to a society free of discrimination, injustice and inequality. But it was also a love story that perhaps only now we are truly beginning to understand. Since Nelson Mandela’s death, the outpouring of grief and remembrance of his outreach and acts of love in South Africa and around the world has been unparalleled. His funeral and burial on Sunday were an impressive showcase by the South African government and the armed forces, interspersed with traditional rituals,” Ranjeni wrote.

“Around midday, the clouds gathered dramatically over Qunu’s impossibly big sky, casting shadows on the hillsides. The Last Post echoed over the valley. Thousands wept, some bit their lips. Through the clouds, military helicopters came into sight, the South African flag fluttering below them. A 21-gun salute shook the earth, billowing smoke… It was done. Nelson Mandela was in his final resting place.”

But though the funeral may have been stately and impressive, it also excluded the ordinary residents of Qunu, among whom Mandela wanted to be buried. They were not welcome at the main event.

There is an image from Greg’s photo reportage that shows village resident Si Ngiyunxe listening to the funeral on his tiny portable radio. “In the background the media centre can be seen, while to his left is the funeral site,” the caption notes. “He grew up on the property adjacent to Mandela’s and is tending to his cows while next door dignitaries pay their respects.”

An invisible wall of military reinforcements saw to it that no unwanted guests got too close, Greg remembers. “You’d walk through the fields and suddenly a soldier popped up, telling you to get back. They were everywhere.”

For journalists, too, there was little hope of getting close to the action. “It’s one of those things where you drive across the country and you’ve got this massive event; and you get there and you realise the guy in Joburg can see more than you. You feel despair. Disappointment. But then you have a cigarette, chat to other journalists, share ideas.”

Greg spent much of the day mooching up and down the grassy lanes, falling in and out of homes, talking to residents. At a house “overlooking the funeral site”, Greg reported, the family weren’t even watching the event on the television broadcast, but “switched it on when asked, out of interest, hospitality, and, like many in the area, in the hope that the media would help them with a quick buck”.

Members of the public who had travelled from across South Africa to be at the funeral watched from a dedicated public-screening area. Perched on a hilltop high above the village, Branko could just about discern a phalanx of abaThembu warriors, marching and chanting in unison. Journalists were among those who broke down and wept: despite the barriers, it was hard not to be moved by all that the moment held. “No ordinary being could love so much and give so completely. How does the Earth bid farewell to a force of nature? Nothing that could have been said or done over the 10-day period of national mourning would have been adequate for South Africa to send off its greatest son,” Ranjeni wrote. “Mandela’s 95 years of life was just too exceptional, too magnificent, too great to capture in memorials and tributes. He gave every part of himself in service to others; his love knew no bounds.”

GoodbiMaverick

The end of 2013 saw iMaverick permanently put to bed with a cover announcing Mandela’s death: “Madiba (1918 – Forever)”. It was the end of the road for Branko and Styli’s fight to remake news consumption via the iPad. For Branko, giving up on iMaverick meant some disappointment – but mainly a sense of huge relief.

“iMaverick was an unfuckingbelievably hard job,” he says. “Worked until 4am, back to bed, up at six. For many months, five days a week. One morning, driving to the office, I felt a brain hiccup just about every minute or two.”

Branko was publishing up to 150 iMaverick pages a day. He had only two designers and a single sub-editor to assist him. Even when iMaverick moved to a weekly effort it was too much.

“I was struggling to stay awake. I was struggling not to faint. I said to Styli, ‘I can’t do this any more’. Styli was very supportive and not entirely surprised when I told him I was out. I was flooded with relief. I felt I was going to die. Literally. Physically. Ah, and you know, iMaverick looked so cool on the iPad, but I’d bitten off more than I could chew.”

Maverick. The Daily Maverick. iMaverick. NewsFire. Daily Maverick.

Branko and Styli’s dream of publishing and sustaining a fearless voice of South African news would live, die and resurrect itself through several incarnations before it finally came of age and established itself as an industry disruptor.

Branko says that someone once told him: “You’re the Uber of South African publishing.” It’s not a comparison he has much time for: “Unlike Uber, we didn’t appear out of nowhere.”

More accurately, Daily Maverick was steadily forged, hour after maddening hour, day in and day out, in the cauldron of blind faith and bruising deadlines.

Now that iMaverick had folded, it was all hinging on Daily Maverick. But if the previous four years had been a battle to navigate the stormy waters of South African media, 2014 would bring with it a tsunami of stress that would see Branko’s health deteriorate drastically and Styli admit to his business partner that he’d “had enough”.